Books of Beasts: From Cambridge to California

Two Cambridge University Library bestiary manuscripts dating from the thirteenth century have made the transatlantic crossing for a spectacular new exhibition that opens today at the Getty Centre in Los Angeles: Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World (14th May-18th August 2019). There they are joined by other bestiaries from major collections around the globe: the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, the Kongelige Bibliotek in Copenhagen, the Bibliothèque royale de Belgique in Brussels and the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, among others. The majority of the exhibits have come from the British Isles, from other repositories here in Cambridge (the Fitzwilliam Museum and Corpus Christi College) and around the country (including the British Library, the Bodleian Library, Aberdeen University Library, Westminster Abbey Library).

Before undertaking their journey, our two manuscripts were both fully digitised and are now available to view on the Cambridge Digital Library. The first is MS Ii.4.26, produced perhaps in Lincolnshire in the early thirteenth-century, and made famous more recently through its translation in 1954 by T.H. White – the author best known for his Arthurian novel, The Sword in the Stone. The second, MS Kk.4.25, perhaps from London and dating a little later, is notable for containing the largest number of painted subjects found in a bestiary. The images online are accompanied by detailed descriptions of their textual and decorative contents, physical make-up and provenances, with a full scholarly bibliography. Introductory summaries by Professor Nigel Morgan and Dr Ilya Dines also set the two books in context, exploring the variations in the content of bestiary manuscripts and identifying iconographic relationships with other artworks surviving from this period (our thanks to Getty Publications for permitting the reproduction of these essays from the exhibition catalogue).

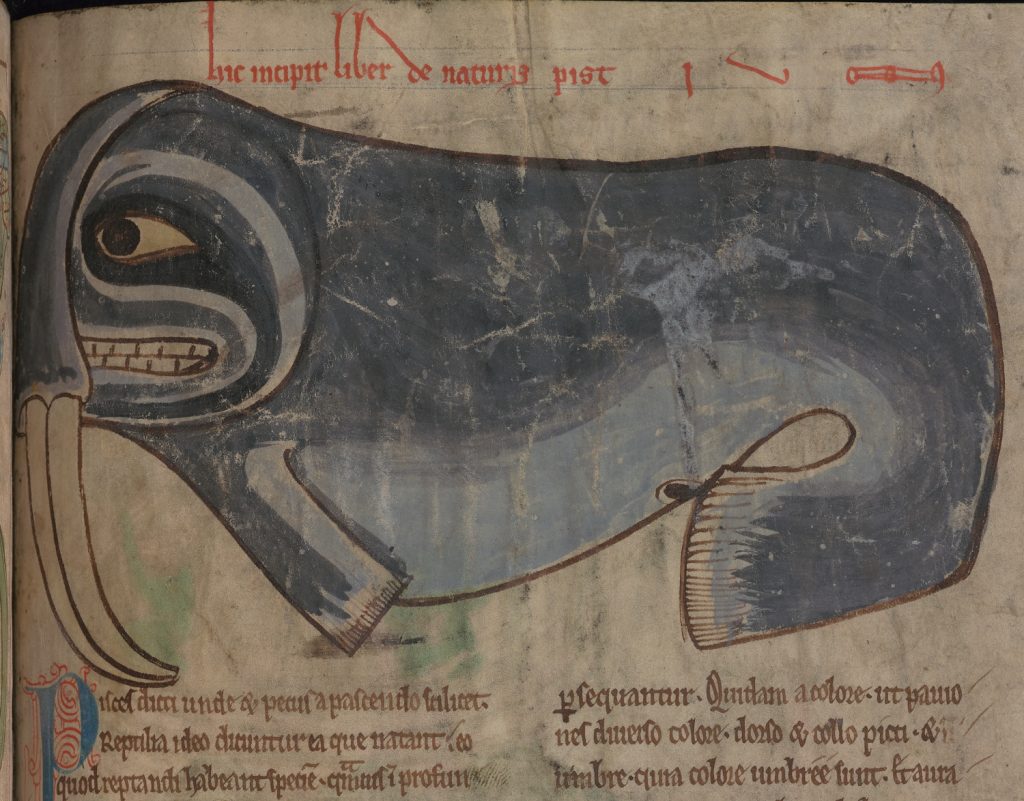

Bestiaries possess an immediate visual appeal: they are among the most heavily illustrated genre of text from the medieval period and depict dozens of animals, real and mythical, sometimes exhibiting their characteristics or behaviours. Scholars have identified various versions – or ‘families’ – of bestiary text, which at root all derive from a combination of sources. These include the Physiologus, a late antique compilation of tales about animals, each with a particular moral attached; Pliny the Elder’s Historia naturalis, mainly accessed via the 3rd-century text by Solinus, Collectanea rerum memorabilium (‘Collection of memorable things’); and Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae, which was written in the 7th century.

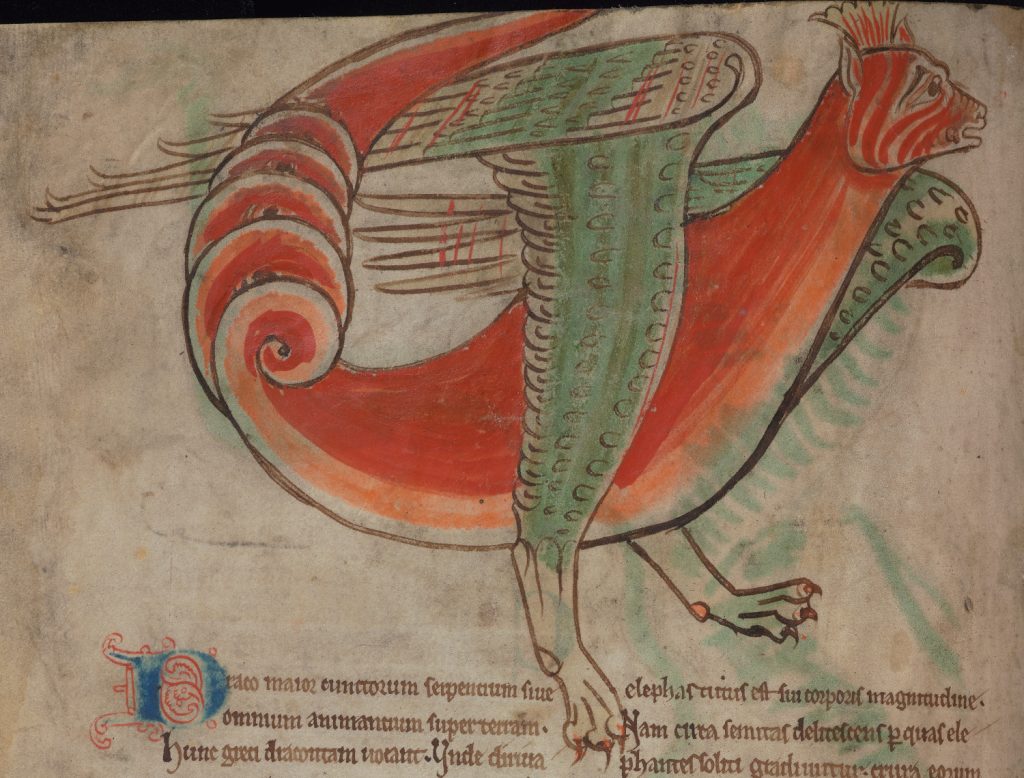

It might seem strange to modern readers that fantastical creatures such as griffins and dragons, hydras and sirens, basilisks and chimeras should take their place alongside the more humble, mundane and familiar cat and dog, sheep and ox, horse and donkey, owl and magpie. However, bestiaries are not natural historical texts. The descriptions and depictions of animals are intended to serve a spiritual, didactic purpose: readers were to extrapolate specific moral or ethical lessons from their physical attributes or behaviour, guided into allegorical reading of the text by choice quotations from the Bible or explanation of the supposed etymology of the beasts’ names.

The fox, for example, which lures in birds by pretending to be dead? He represents the Devil: ‘To all those living by the flesh he pretends that he is dead, until he has them in his maw and punishes them. Yet to spiritual men in faith he is truly dead and reduced to nothing.’

The panther, meanwhile, is like Jesus. After the panther has eaten, it hides in its cave and sleeps – ‘but after three days it rises, emits a great roar, and from its mouth comes forth a very sweet odour like all spices. Moreover, when the other animals hear his voice, and because of the sweetness of the fragrance, they follow him wherever he goes. Only the dragon, however, hearing his voice with fear, flees terrified into the hollows of the earth…Thus, our Lord Jesus Christ, the true panther, descending from the heavens, delivered us from the power of the Devil…’.

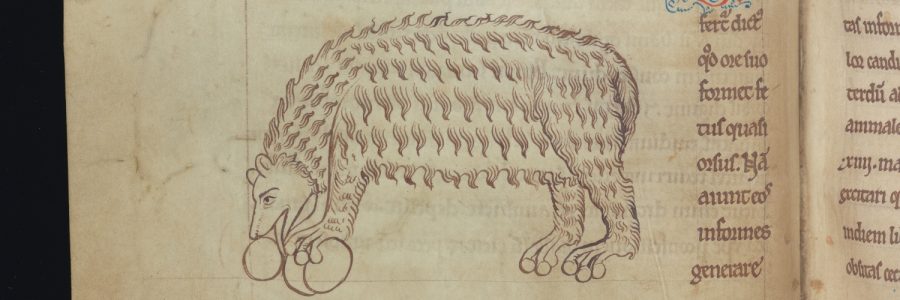

Some animals provide an example to follow: the beaver, for instance. (Trigger warning: male readers may wish to skip this section). The beaver – known by his Latin name castor – is ‘a very gentle creature…whose testicles are extremely useful for medicine’. According to the Physiologus, when the beaver knows he is being hunted, he gnaws off his own testicles and throws them at his pursuer in order to make his escape. ‘Thus,’ the bestiary concludes, ‘any man who is turned toward God’s command, and wishes to live chaste, cuts himself off from all vices, and all acts of lewdness, and tosses them into the Devil’s face…’.

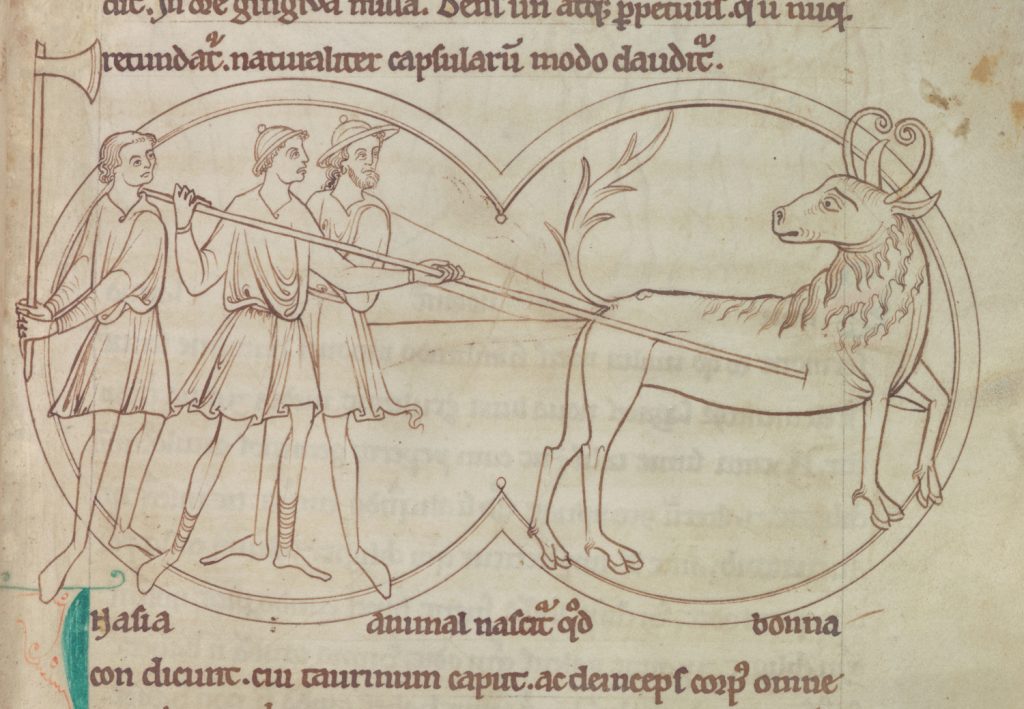

There are other creatures that the bestiary advises one should avoid. The crocodile is ‘armed with fierce teeth and claws, and has skin so hard that although a blow with a hard stone strikes its back, that does not harm it’. The manticore, which has three sets of teeth and a pointed tail like a scorpion’s, ‘very zealously seeks human flesh. Its feet are so strong, its leaps so powerful, that neither the broadest space nor the widest barrier can hinder it’. The bonnacon, meanwhile, with a body like a bull’s and a mane like a horse’s, seems harmless enough at first glance. However, when attacked, ‘it emits a discharge from its behind three acres in length, using an overflow of the large intestine, an emission so hot that scorches whatever it touches’. It is not clear exactly what lesson one should draw from this, other than that one should definitely not get on the wrong side of the bonnacon – literally.