Medieval Chapbooks – Early collecting of Rabbi Judah ha-Levi’s poetry: T-S 13J24.13 and T-S K25.138

The itinerary of Rabbi Judah ha-Levi – the famed twelfth-century Spanish rabbi, philosopher, courtier and poet – puzzled scholars who tried to trace his journey from Toledo to Granada to Alexandria and eventually to the shores of his beloved Zion. And while the Genizah has famously assisted in understanding ha-Levi’s travels,[1] the collection has much to offer in reconstructing the journey of ha-Levi’s poetry as well.

Two documents from the Cairo Genizah, T-S 13J24.13 and T-S K25.138, offer a glimpse into the dissemination of ha-Levi’s secular poetry in particular. Both fragments contain Hem Hem Yeme Tevel ve-Leleha (‘These, These are the Earth’s Days and its Evenings’) in the qaṣīda form of a long, monorhymed poem, with 44 lines prosodically joined by the repeating ending ליה. Like all qaṣīdas, the ode is structured with a nasīb and madīḥ joined with a taḵalluṣ– prelude and praise woven together by rhetorical transition.[2] First, Lady Earth is depicted as a stunning but unreliable mistress; one of her primary contributions, Wine, is beautiful but ultimately a source of folly; and finally, Wisdom (through Song) is praised above all, and Judah ibn Tibbon (the recipient of this poem) is glorified as its mouthpiece. The poem overflows with striking imagery: the Earth wears sumptuous robes made of dew drops and golden-tinted flowers, and Wine is depicted as a sparkling maiden in a crystalline garment (the glass goblet).[3]

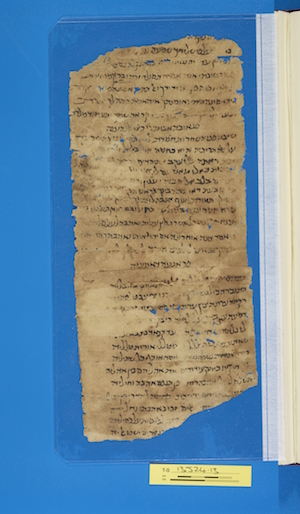

Cambridge University Library T-S 13J24.13 recto

The appearance of this poem in two different fragments can help contextualize the early transmission and collection of ha-Levi’s poetry. The most comprehensive sources for Rabbi Judah ha-Levi’s poetry are the Maḥane Yehuda diwān, redacted by the twelfth-century judge Ḥiyya al-Maghribī and the later, thirteenth-century collection compiled by Yešuʿa ben Eliyahu ha-Levi (alphabeticaly arranged by rhyming letter). The St. Petersburg Firkovich Collection in the Russian National Library also contains diwān fragments, among them a number of poems and Arabic superscriptions not included in the Ḥiyya or Yešuʿa manuscripts, but ones that may have circulated in Alexandria after the poet’s stop-over in the city. Patrons frequently copied their poets’ poems, and prior to the compilation of the Ḥiyya diwān, poems would have also been passed on by ‘tradents’, people who recited poems from memory.[4]

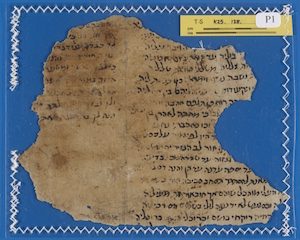

Fragments from the Genizah are uniquely positioned to shed light on the early composition and collection of ha-Levi’s poems. As Yahalom writes, ‘The great importance of the Cairo Genizah fragments is due in large part to their age: even the earliest complete manuscripts from the diwāns of the poets of Spain are comparatively late in relation to the Genizah fragments and booklets… it seems possible to argue that any manuscripts from the region in which the poet is mentioned with a blessing for the living were not only edited and collected but also transcribed before the middle of the twelfth century and prior to, or at least a short while after his death.’ (Yahalom 202). T-S 13J24.13 contains a Judaeo-Arabic superscription from the ageing translator Judah ibn Tibbon, wishing ha-Levi a long life (placing the fragment’s copying during the poet’s lifetime), in addition to framing ha-Levi’s poem as a response (in similar metre) to one about old age and praising ha-Levi’s skills. The Hebrew segment at the top of the fragment may further our understanding of the ordering of the poems, and the context of their writing. The reappearance of ha-Levi’s poem in T-S K25.138 in a codex with other Judaeo-Arabic writings can also add to our understanding of poetry-collecting in personal correspondence and papers. These fragments thus invite us to study the travels and transmission of ha-Levi’s work.

A leaf from Cambridge University Library T-S K25.138 recto

Footnotes

[1] See Goitein (1959); Yahalom (1995); Scheindlin (2008) and Friedman (2013).

[2] The basic unit of the Spanish medieval Hebrew poem was the bayt (lit. house), a line broken down into two, usually symmetrical, hemistitches – the initial delet (door) and the closing soger (lock). The soger contained the rhyme to be sustained throughout the poem.

[3] Samuel Bernstein’s translations of Haim Brody’s editions, and Samuel Phillip’s translations of Samuel Luzzatto’s editions were valuable in the interpretation of this poem.

[4] This role is discussed by Shirmann in “The Function of the Hebrew Poet in Medieval Spain” (251).

Bibliography

Bernstein, Simon, and Brody, Heinrich, eds. Shirei Yehuda Halevi. New York: Ogen Publishing House of the Istadruth Ivrith, 1944.

Cole, Peter, ed. The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. The Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation.

Elizur, Shulamit. Shirat Ha-Ḥol Ha-ʻIvrit Bi-Sefarad Ha-Muslemit. Ramat-Aviv ; Tel-Aviv: ha-Universiṭah ha-petuḥah, 2004.

Friedman, Mordechai Akiva, Ḥalfon and Judah ha-Levi. The Lives of a Merchant Scholar and a Poet Laureate according to the Cairo Genizah Documents. Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 2013.

Goitein, Shelomo Dov. ‘The Biography of Rabbi Judah Ha-Levi in the Light of the Cairo Geniza Documents.’ Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 28 (1959): 41–56. JSTOR. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

Philipp, Samuel. Samtliche Gedichte Abu’L Hassan ‘Jehuda Ha-Lewi’ Nach Den Divan’s R. Jeschuah Ben Eliah Halevy U. R. Chija Almagrevi Mit Den Glossen von Prof. S. D. Luuzzato. Vol. 1. Lemberg: F. Bednarski, 1888.

Scheindlin, Raymond. The song of the distant dove: Judah Halevi’s pilgrimage. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Schirmann, Jefim. ‘The Function of the Hebrew Poet in Medieval Spain.’ Jewish Social Studies 16.3 (1954): 235–252.

Yahalom, Joseph. ‘Diwan and Odyssey: Judah Halevi and the Secular Poetry of Medieval Spain in the Light of New Discoveries from Petersburg.’ Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos (1995): 23–45.

---. Yehuda Halevi: Poetry and Pilgrimage. Jerusalem: the Hebrew University Magnes Press, 2009.

Cite this article

(2015). Medieval Chapbooks – Early collecting of Rabbi Judah ha-Levi’s poetry: T-S 13J24.13 and T-S K25.138. [Genizah Research Unit, Fragment of the Month, February 2015]. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.8234

Contact us: genizah@lib.cam.ac.uk

The zoomable images are produced using Cloud Zoom, a jQueryimage zoom plugin:

Cloud Zoom, Copyright (c) 2010, R Cecco, www.professorcloud.com

Licensed under the MIT License