Slavonic item of the month

This initiative aims to celebrate the diversity and riches of the UL's Slavonic collections. Each month, the Slavonic staff of the UL will either choose an item connected to a current event or an anniversary falling that month, or an item of particular interest which they have come across in their usual work. Each item chosen will be celebrated with a photo and a brief description.

A few weeks ago, we were fortunate enough to receive a donation of five lovely books from the Kharkiv-based publisher Oleksandr Savchook and the organisation Progress-14.

The five donations add to the 12 Savchook titles we had previously bought and which were published between 2014 and 2021. The five new publications, which reflect the core strengths of Mr Savchook’s publishing house in terms of their concentration on the arts, were published in 2022 and 2023 and make very welcome additions to Cambridge’s Ukrainian collection.

Read more...

Kyivan Christianity – 14 new volumes

While the Ukrainian Christmas largely joined the western Christmas in 2023, this Easter will still see a substantial difference, with the western churches celebrating Christ’s resurrection in March and Ukrainians celebrating in May. Nevertheless, the Easter weekend for most in Cambridge seems a good time to mark the arrival of many new volumes in the Kyivan Christianity set.

Read more...

Books about stamps are not a huge business in modern purchasing at the University Library, but they can be incredibly interesting to more than the dedicated philatelist. We recently bought two volumes about Ukrainian stamps more for the principles and attitudes reflected in the stamps than for the images themselves. What inspires a government agency in its selection of images? It’s a particularly keen question when it comes to a country whose last 10 years have seen parts of its territory overtaken by illegal annexation and ruined by a growing war.

Read more...

Ukrainian ceramicist Olʹha Rapaĭ-Markish

The 2018 publication Olʹha Rapaĭ-Markish arrived in Cambridge later that same year but I only recently managed to take a proper look. Olʹha Rapaĭ-Markish (also known as Olʹha Rapaĭ or the anglicised Olha/Olga Rapay), 1929-2012, was a Ukrainian artist most known for her ceramics, large and small, and this book explores her often tragic life and her delightful work. [Note that her father, Peret︠s︡/Peretz Markish, the major Yiddish writer who was shot in Moscow in 1952 during the Night of the Murdered Poets, features in the book, and that we have other books by/about him here.]

Read more...

Our last Slavonic item of the month for 2023 is a newly purchased ebook about the history of books and printing in Ukraine. Z istoriï knyz︠h︡kovoï kulʹtury Ukraïny [From the history of the book culture of Ukraine] looks at items in the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine. It contains the following 4 main sections, which contain a total of 15 chapters. I give the 3 chapters that fall under the all-important library section.

Read more...

This month, the Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics Faculty Library and the UL received their copies of the 2023 book Mova-mech : i︠a︡k hovoryla radi︠a︡nsʹka imperii︠a︡ [Language-sword : how the Soviet empire spoke] by I︠E︡vhenii︠a︡ Kuzni︠e︡t︠s︡ova. The book had been requested by the Language Teaching Officer in Ukrainian at the Faculty, and the libraries had agreed to buy a copy each.

The 374-page book contains 87 short chapters covering the history and various aspects of Soviet language policy and its effect, including on Ukraine and Ukrainian. The book’s table of contents can currently be seen as snapshots on the publisher’s page for the title. Here are the Library of Congress subject headings we used in the catalogue record, linked to take you straight to an advanced search in iDiscover for each heading. Note that the last two are headings which are not subdivided geographically, hence looking very general but still useful to have in the record.

Read more...

Dovzhenko in the files of the secret services

Another newly added title to the catalogue is a 2-volume set of sources from Soviet secret service archives about the filmmaker Oleksandr Dovz︠h︡enko. I’ve written before about our holdings about Dovz︠h︡enko (eg here) but this new arrival is a significant addition and warrants its own blog post.

Read more...

Some courses have already started in the University, but the majority commence next week, with students in the process of travelling to Cambridge and their lecturers in the process of completing preparations for them. We are therefore currently in a relative lull in terms of book borrowing, but I thought it would be interesting to take a look at what Ukrainian/Ukraine-related books Cambridge’s readers have got out on loan. (Note that the data is only about print books, not ebooks)

Read more...

Early Soviet Cinema Collection and Ukrainian film

At the tail end of the 2022/23 academic year, we were able to buy access to East View’s Early Soviet Cinema Collection, which provides digitised copies of 119 books published between 1897 and 1948. At the moment, there are only very brief author/title records for most of these but current University members can browse them all directly on the East View platform.

“Soviet” can often mean Russian, rather than anything more representative of the Soviet Union; that’s largely the case here. But while the collection is fully russophone, there is at least some diversity in terms of subject matter, as an examination of the collection’s contents show when looking in particular for coverage of the hugely important Ukrainian film industry.

Read more...

The Ukrainian city of Kherson has often been in the headlines since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Kherson was occupied in early March 2022, but many of us will remember inspirational footage of its citizens demonstrating against the Russian occupiers, waving Ukrainian flags and singing Ukrainian songs. September saw the Kherson Region (Khersonsʹka oblastʹ) claimed by Russia to have been legally annexed in an internationally condemned move, while Kherson’s liberation by the Ukrainian army took place in November. Recovering from months of occupation and destruction, Kherson then suffered seriously from flooding and pollution caused by the June 2023 destruction of the Kakhovka dam.

Our latest Slavonic item of the month is a 2023 anthology of poems by Kherson inhabitants about their city and region and the war.

Read more...

The provider East View has recently started to stock Ukrainian ebooks that libraries can buy (libraries require special licensing), and we recently bought an initial 30 volumes, including a couple of Crimean Tatar titles that I wrote about in another post and don’t cover again here.

All the books listed in the table were published in Kyïv or Kharkiv. Except for a few in English translation, they are all in Ukrainian. The list displays a little clumsily since the blog software doesn’t much like Excel formatting, but I have given rough section headings and there are four columns for the book entries: title, author/editor, date, URL to take Cambridge readers straight into the book.

Read more...

A new volume of Mykhailo Hrushevs’kyi’s works

This week, another volume was added to the 50-volume Tvory (Works) set by Mykhaĭlo Hrushevs’kyĭ that has been being published since 2002. The new volume said it was v. 34, v. 6, and it contains part of Hrushevs’kyĭ’s epic history of Ukraine-Rusʹ. Having taken the numbers at face value, assigning the number as v. 34(6), I increasingly suspect that the v. 6 referred to on the title page will turn out to be preceded by v. 1-5 in the set’s v. 29-33 rather than all within a massive v. 34. Ah well – labels can be reprinted and metadata updated when we know for sure.

Read more...

This morning, I had the satisfaction of solving the problem of a missing Ukrainian book. It hadn’t been missing in the normal library sense of not being on the shelf. Instead it was entirely missing from the catalogue.

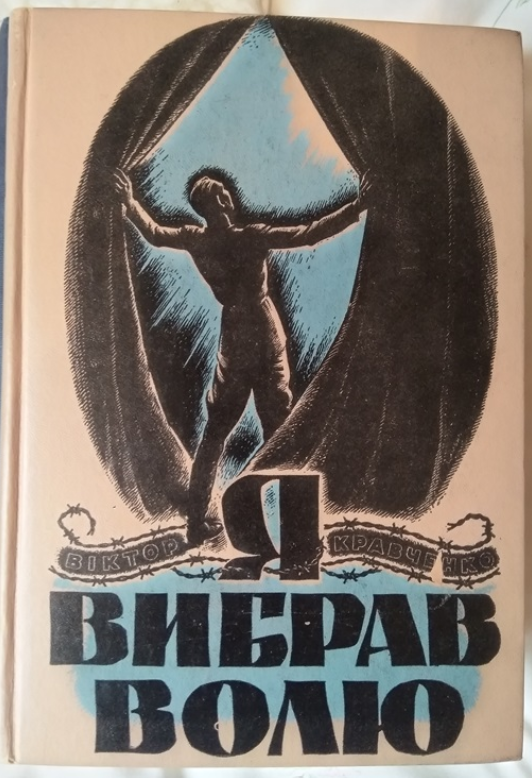

A little while ago, a colleague sent me a few photos of covers of Ukrainian literature and history books in the University Library, and among them was this:

Read more...

New arrivals about the Russo-Ukrainian war

Among a good number of new Ukrainian books that arrived in March are of course many about the Russian war against Ukraine taking place since 2014 which then intensified appallingly with the full-scale invasion launched in February 2022.

Many of these titles look at Ukraine before February 2022. One is the three-volume set Khronika viĭny 2014-2020 (Chronicle of the war 2014-2020). Across the set, the authors, Oleksandr Krasovyt︠s︡ʹkyĭ and Dar’i︠a︡ Bura,cover: the Maidan events to the Battle of Ilovaĭsk (v. 1), from the first Minsk Protocol to Minsk II (v. 2), and the following 5 years of hybrid war (v. 3). We plan to buy the English translation of the set as ebooks.

Read more...

This brief post looks at a couple of welcome donations of books about Ukrainian art.

At the front line : Ukrainian art, 2013-2019 is the catalogue of an exhibition of 13 Ukrainian artists that took place at the National Museum of Cultures in Mexico City in 2019 and the Oseredok Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Centre in Winnipeg in 2020. One of its editors and contributors, Dr Svitlana Biedarieva, kindly arranged the donation of a copy to the UL, and we are very glad to add it to our collections, for its examples of and insights into artistic experience of the pre-2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and the role of art and artists in the context of war. The catalogue is largely textual, with the text provided in Spanish, English, and Ukrainian. Some of the pictures in the catalogue are shown below, with the table of contents. It is worth mentioning that Cambridge readers also have access to Dr Biedarieva’s 2021 edited volume Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic art : political and social perspectives, 1991-2021.

Read more...

A Ukrainian almanac for 75 years ago

As the first month of the new year draws to a close, it felt appropriate to look at Ukrainian kalendar’ al’manakh for 1948, 75 years ago.

On its title page, it describes 1948 as a jubilee year, and refers back to the three years of 1648, 1848, and 1918. 1648 saw the start of the Cossack uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which would eventually lead to the creation of the Cossack Hetmanate state. Two centuries later, Galician Ukraine was in the Austrian Empire, and 1848 saw the creation of the Holovna Rus’ka Rada (Supreme Ruthenian Council) in L’viv, which determined the blue-yellow flag Ukraine uses to this day and oversaw the publication of the first Ukrainian-language newspaper, Zoria Halytska (Galician Star, or Galician Dawn). 1918 saw immense changes in Ukraine, starting with the 22 January declaration of the independent state of Ukraine.

Read more...

This September, Thames & Hudson published Treasures of Ukraine, with proceeds going to charity. The book is not yet available through the UL, but we expect a copy from the publisher through legal deposit in 2023.

The book is a beautifully illustrated introduction to the history and culture of Ukraine, with an introduction by the famed writer Andrey Kurkov (whose 2022 Diary of an invasion we have recently purchased as an ebook). Here are the contents of Treasures of Ukraine:

Read more...

The fourth Saturday of November is Holodomor Memorial Day, which marks the loss of millions of Ukrainians in the man-made famine of 1932/33. Today, of course, the day of remembrance occurs during another man-made horror in Ukraine, as Russia’s war continues to take a terrible toll on Ukraine and Ukrainians.

We marked the 80th anniversary of the Holodomor in 2013 with a blog post about one particular book (here) and wrote again about the Holodomor in 2019, when the libraries put on a pop-up exhibition to tie in with a Cambridge Ukrainian Studies screening of the film ‘Mr Jones’ about the Welsh journalist whose unflinching reports of the horrors he saw were too easily ignored (blog post here).

Read more...

The problems of successful upbringing

This month’s item is yet another lovely arrival through the donation from the New York Shevchenko Scientific Society Library. Problemy uspishnoho vykhovanni︠a︡ provides a 20-chapter guide to raising children. Vykhovanni︠a︡ can also mean education, but the chapter list makes it quite clear that the book is about bringing children up more generally. The book covers birth and new parenthood, first steps and nursery, some coverage of early school years, general topics such as behaviour, interest, authority, and music, and the spiritual education of children. There are also chapters about language and about nurturing national consciousness in the family – both interesting since the book was written and published in the US with the Ukrainian diaspora its primary audience.

Read more...

Today, the day when Putin added to his illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014 the illegal annexation of four more Ukrainian regions (not fully even under temporary Russian control) following further referenda not worth the paper they were falsified on, our weekly Ukrainian blog post promotes new writing about Russia’s war against Ukraine made possible by the Ukraine Lab initiative, led by the Ukrainian Institute in London.

Read more...

Ukraine and films in the Klassiki database

Last year, Cambridge University Libraries started providing access to the Klassiki database of films from Eastern Europe, Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. The subscription was started specifically to support courses taught under the auspices of Film Studies and/or Slavonic Studies. In its own words: “Klassiki hosts a highly curated permanent collection of films that represent the best of classic filmmaking from the region. We also offer a brand new ‘Pick of the Week’ contemporary title, selected by the curatorial team. Each of our films are accompanied by programme notes, journal essays, newly commissioned subtitles and online interviews with the best filmmakers from the region.”

Read more...

Newly catalogued Ukrainian books

In my previous post, I made reference to the quite amazing news that we are expecting new book arrivals from Ukraine in the near future. This brief post draws the attention of our Ukrainian-reading followers to some of the last books we had received from our supplier.

Read more...

All of us have learned the names of Ukrainian cities and towns from the shocking and heartrending news about Russia’s war against Ukraine, and the name of Mariupol has appeared probably most frequently of all. This blog post – written while desperate attempts continue to be made to arrange safe passage at least for the civilians in the besieged Azovstal factory complex – looks at a map of Mariupol from 1967.

At that stage, Mariupol (Маріуполь) had another name, being one of many places renamed in the Soviet period after Soviet politicians – in Mariupol’s case after Andreĭ Zhdanov (1896-1948), who was born in the city. This map, then, has the city as Zhdanov (Жданов), which name it held from 1948 until 1989.

Read more...

Ukraine’s forgotten war before war

Something that many people have been keen to point out since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine last month is that Russia and Ukraine had already effectively been at war since 2014, as Russian-backed separatists fought alongside Russian soldiers against the Ukrainian army in the Donbas (short for Donetsk Basin) in the east of Ukraine.

We have written blog posts before about the material the UL has collected about this conflict, as well as about the annexation of Crimea, and books have continued to come in about it. Just today, my colleague catalogued Na shchyti : spohady rodyn zahyblykh voïniv (On the shield : memoirs of the families of fallen soldiers), a 3-volume set of memoirs collected and told by the journalist Iryna Vovk.

Read more...

There had been other plans for this month’s blog post, but Putin’s invasion of Ukraine yesterday and its unfolding violence and tragedy are all any of us can think about now.

In this blog, we normally point readers to books but of course in the current situation, books will follow and internet resources are what we need for information now. This list put together by a New Mexico State University academic of freely available news sources in English from Ukraine, Russia, and more is a good starting place.

Read more...

Asian and Middle Eastern material in Russian

Having had the privilege of being on the selection panel for the new Chinese Specialist recently, I was pleased this week to catalogue the latest additions to the enormous Pami︠a︡tniki pisʹmennosti Vostoka (Written monuments of the East) set which stands at 820.b.20. The set contains Russian translations and commentaries of major texts from across Asia. Among the new additions were a set of papers by the 16th-century Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin, the second volume of a dictionary of Turkic words, and a translation of the Mahāvairocanasūtra, a core Buddhist text whose original Sanskrit is lost so the Russian comes from the 8th-century Chinese translation. These new additions are volumes 148, 128(2), and 149 respectively.

Read more...

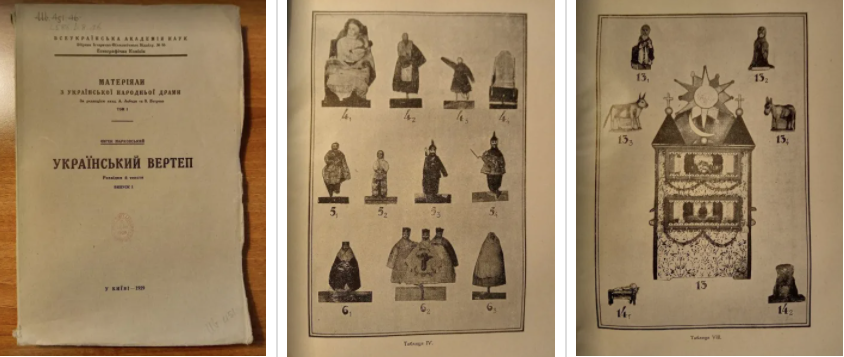

The nativity in Ukrainian puppet plays

The Institute of History of Ukraine in its online encyclopedia (in Ukrainian) explains that the vertep, a telling of the Christmas story through puppet theatre, is thought to have appeared in the second half of the 17th century and lasted until the early 20th century. In 1929, I︠E︡vhen Markovsʹkyĭ published a book about vertep which was due to be the first volume of a set but which was never added to. The UL’s copy has its record here.

Read more...

Finding Balmont’s hand in a UL copy

This guest blog post is written by one of our UL Reading Room colleagues. David, also a learner of Russian, came across a hidden treasure in our older collections – a book of poetry by the poet Bal’mont (normally Balmont in English, as below) with inscriptions by the author.

Konstantin Dmitriyevich Balmont was a well known poet of the Silver age of Russian Literature. The last book he completed, Свѣтослуженіе (Svi︠e︡tosluzhenīe; Liturgy of light), was published in Harbin, Manchuria in June 1937 to coincide with Balmont’s 70th anniversary.

Read more...

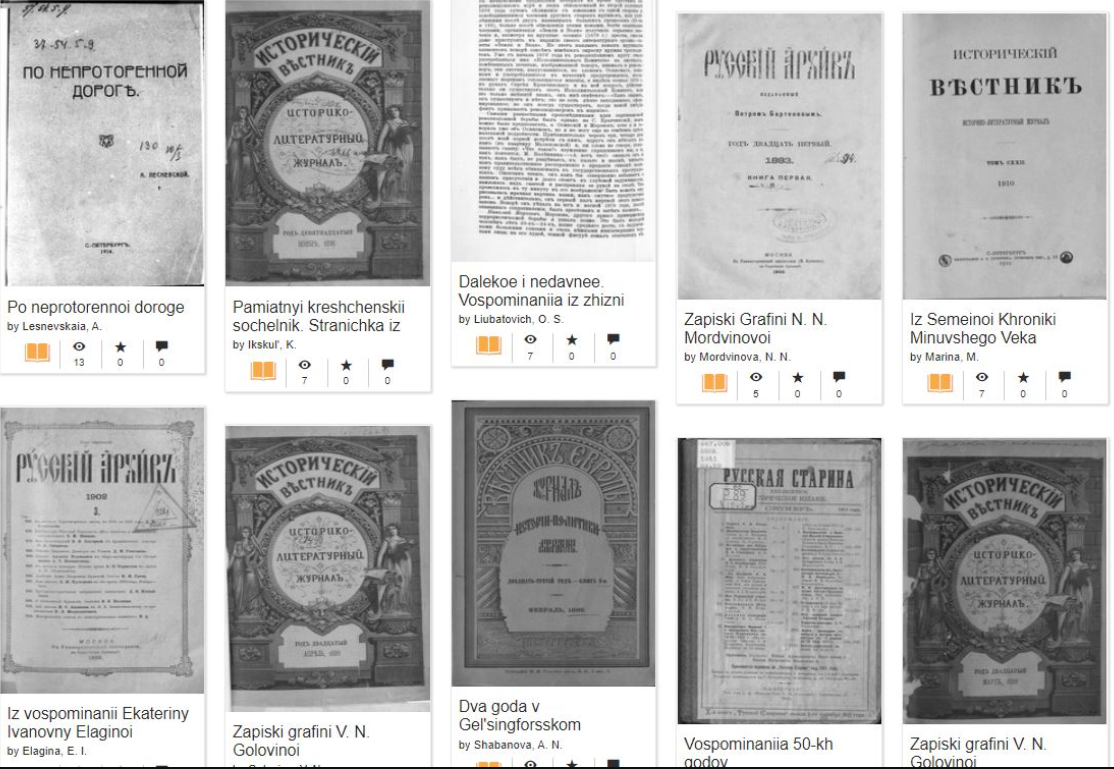

‘Memoirs of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Women’ online collection

Last year, I wrote about the first books to be catalogued from a donation sent to us by the Shevchenko Scientific Society in New York. Today’s post looks at several other books in the collection which passed through my hands last week.

As I explained in the previous blog post, the majority of the donated books (many of which are fairly fragile) would go to Cambridge’s Library Storage Facility, from which they can be recalled to be consulted in the University Library. When books are sent to the LSF, their records are suppressed from iDiscover – if ours is the only copy – until they have arrived there. Since our department’s workflow involves books destined for the LSF going there only in occasional batches, most of the Shevchenko donations are yet to appear in the catalogue. I’m afraid you will have to take my word for the fact that dozens of these donations will appear in iDiscover when the next delivery from us to the LSF takes place – probably within the next week or so.

Read more...

‘Memoirs of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Women’ online collection

This short September Slavonic blog celebrates a new open-source collection of women’s memoirs from the last 70-odd years of the Russian Empire. The collection has been put together by the University of Illinois’ extraordinary Slavic Reference Service (SRS). The SRS provides help to researchers all around the world, and you can read about them and their brilliant work here.

Read more...

Completing Miłosz, and other new Polish books

Our long-suffering Polish suppliers took a rush of orders in late June with their usual good grace, despite the need to supply them before the end of our financial year little more than a month later. Among the resulting new arrivals is a particularly exciting addition – the two-volume Wygnanie i powroty : publicystyka rozproszona z lat 1951-2004, a collection of Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz’ articles in the press, one of whose editors and contributors is Dr Stanley Bill of MMLL’s Slavonic Studies. The publication was many years in the making, as Miłosz pieces published all over the world were carefully brought together. The significance of the nearly 2,000-page-long set means it has been granted what is still a pretty rare post-lockdown open-shelf classmark. The vast majority of our new arrivals continue to go into the closed but borrowable C200s class, to help us deal promptly with incoming books while still having our numbers in the physical office significantly capped .

Read more...

Sporting memorabilia from the Russian Empire

This is an unwittingly Olympics-related blog post. During a recent day spent processing new Slavonic arrivals in the UL, I kept an eye out for potential subjects for the July blog post – and the winner happened to be an album of sports medals and badges held by the Historical Museum in Moscow. Sportivnye zhetony i znaki Rossiĭskoĭ imperii iz sobranii︠a︡ Istoricheskogo muzei︠a︡ contains colour photos of the front and reverse of hundreds of sporting awards and sport society membership badges presented in the Russian Empire or to the empire’s citizens outside its boundaries. The pairs of images are accompanied by captions providing a physical description and brief context if known, along with the date of acquisition by the museum and inventory number.

Read more...

Ukrainian ebooks about the 2001 census

This week, we have purchased 30 ebooks of statistics and analysis about the 2001 Ukrainian census which provide an important snapshot of Ukraine within its first post-Soviet decade. 29 of the the 30 are in Ukrainian and represent our first ebooks in that language (there remain few Ukrainian ebook options for institutions in general), and 12 of the 30 focus on data for Crimea specifically.

Read more...

Cambridge staff and students now have access to nearly 10,000 Russian ebooks, through a newly started subscription to BiblioRossica’s Leading Russian Scholarly Presses package.

Read more...

Ukrainian church history (and Rowan Williams)

These ends of months really do come along very quickly. Too quickly in this instance, so we’re a day late – apologies. This post looks at material in the light of the forthcoming Cambridge Ukrainian Studies event ‘Church Matters: a conversation between His Grace Rowan Williams, Archbishop Emeritus of Canterbury, and His Beatitude Sviatoslav Shevchuk, Major Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church‘ which will take place online on Friday 7 May at 6pm (open to all, but do register in advance).

Read more...

Last month’s Slavonic blog post looked at recently received new Polish publications, including a book of poems by Adam Zagajewski. Little did I think then that a month later I would be writing about the poet in the light of his sad death at the age of 75.

Adam Zagajewski spent most of his life in Kraków but was born in what is now Ukraine. He was born in June 1945 in a Lwów that was still chiefly Polish, but he and his family were caught up in the enormous WW2 population transfers as national borders shifted. Polish Lwów became Ukrainian L’viv – just as German Gleiwitz reverted to Polish Gliwice, where Zagajewski’s family moved to and where he grew up. One of the volumes of poetry we hold in the UL by Zagajewski is called Jechać do Lwowa (To travel to Lwów), and one of our books of essays by him is called Dwa miasta (Two cities; the English translation is also in Cambridge). The fate of his family and their home and the fate of millions of other similarly displaced families cast a long and complex shadow.

Read more...

Polish books have been in the press this month – for cheering reasons (the announcement that Olga Tokarczuk’s >1000-page The books of Jacob will published in translation later this year) and for very worrying reasons (the ruling against the writers of Dalej jest noc, a two-volume work about the fate of Polish Jews during the war: a ruling that threatens further Holocaust research). The UL’s copy of Dalej jest noc is at C214.c.8947-8948 and our copy of the Polish original of Tokarczuk’s epic is at C210.c.2501.

Read more...

‘Soviet woman’ digital archive on trial access

As the Electronic Collection Management team announced in this blog post, Cambridge readers with Raven accounts now have trial access to the East View digital archive of Soviet woman. The first issue came out in late 1945. Its introduction discussed the purpose and place of this new bi-monthly title, saying “Soviet Woman is a new illustrated literary, art, and socio-political magazine whose purpose is to deal comprehensively with the work of Soviet women in industry and their part in social, political and cultural activities. Our magazine will study and summarize in the light of peacetime problems the experience gained by women during the war”.

Read more...

Items from the postcard collection put together by the late Catherine Cooke have featured in previous posts, including a Soviet-era New Year card. This time, a little group of pre-revolutionary Christmas cards forms the December Slavonic item(s) of the month.

Read more... and detailed description of the cards...

Ukrainian donations from New York

This summer, I received five boxes of donations from the Shevchenko Scientific Society in the United States. The Society had offered duplicates to libraries around the world, and we were fortunate enough to receive a few hundred with the help of the Cambridge Ukrainian Studies programme which paid for delivery. While we have avoided having library material delivered to our homes, these boxes did come to my house with the agreement of the Society and the CUS programme lead, because timing was of the essence and the University Library building was at that point not fully open for deliveries.

Acquiring ebooks from Eastern Europe and former Soviet states is by no means a straightforward business. A great deal of publishers across this enormous area publish only in print. Those who do produce ebook versions may not produce these for institutional purchase. As our readers probably know, even if an ebook is available for an individual to buy, it may not be available for libraries to buy.

It is easy to tell that a cataloguer has struggled with a set when its classmark sequence comes out as 758:53.c.201.33(1a-1c,2a-2h,4c-4d,5a-5b,5e-5f,5i,6a-6b,7a-7c). This was one of the last things I catalogued before lockdown, and provides the beginnings (and hopefully more!) of the Library’s fine new set of Bolesław Prus.

The importance of open access (OA) publishing has been made clearer than ever during recent and ongoing physical library closures. For some years now, the OstDok repository has provided students and scholars working on Eastern Europe with vast amounts of OA material. OstDok is a collaborative product, with the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek and the Herder-Institut in Marburg among the main partners. I have had the pleasure of hearing my colleague Dr Gudrun Wirtz at the Staatsbibliothek discuss OstDok at conferences and seminars in the past, but my appreciation of the work she and others have put into the resource has never been greater.

This lovely item is still waiting for me to complete its catalogue record in the UL, but happily I captured many of its contents in photographs on a memory card I brought home on our last day in the Library.

This month, I wanted to draw attention to a growing open access resource called Prozhito which provides diaries written by the great and the good and the ordinary. At the time of writing, Prozhito (“Lived”, the passive past participle) contains diaries in Russian by 5755 authors, in Ukrainian by 104, and in Belarusian by 58.

May 2020

Having initially wanted our lockdown-era posts to focus on e-available material only, I am now going one step yet further away myself by writing about books held by the UL neither electronically nor physically… This post instead looks at Slavonic translations of British detective fiction I have picked up for myself over the years. Getting used to reading in another language can take time, and I for one found that worrying about the plot as well as the words really held me up. What I came to discover was that reading a familiar detective novel translated into the language took the pressure off, and it’s a trick I have stuck to ever since.

April 2020

Russian ebooks are a novelty for Cambridge, and it is fantastic that our University staff and students can now try out three ebook platforms supplied through the vendor MIPP until 1 June. This blog post gives an overview of the databases. Do please give feedback about any/all of them.

March 2020

March has already finished? This blog post is late?? It is not so easy to tell at the moment… The subject of this post, the early geneticist William Bateson (1861-1926), might have considered my disorganisation a “trait”. What must he have thought of the avant-garde when he visited Soviet Russia?

Painting the nightmare of Auschwitz

This year will see many 75th anniversaries relating to the Second World War, and one of the most poignant – the liberation of Auschwitz by the Soviets – has already occurred, in late January. We recently received an important addition to Cambridge’s significant holdings about the Holocaust and Auschwitz in particular, in the form of a catalogue of works by David Olere, Ten, który ocalał z Krematorium III (The one who survived Crematorium III), based on an exhibition held at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in 2018-2019.

The introduction to the 1945 ‘Select classes classification’

The University Library’s classification schemes can sometimes seem designed to hinder rather than aid the reader. This post looks at some recent and lovely East European additions to the S3-figure class and briefly explains its history and current use.

Earlier this year, the Friends of the National Libraries generously funded the purchase by the University Library of a 1648 book called Kniga o vere edinoi istinnoi pravoslavnoi [Book on the one true Orthodox faith]. The volume, bought from a major dealer, had latterly been part of the Macclesfield library at Shirburn Castle in Oxfordshire.

This exceptionally rare book of Orthodox liturgy and theology in Old Church Slavonic is an exciting addition to the collection of early Slavonic books found across collegiate Cambridge. Much of the content is is derived from the earlier writings of Zakhariia Kopystens’kyi, Archimandrite of the Kyivo-Pechers’ka Monastery. The book, printed by Stefan Boniface (Stefan Vonifat’ev), a prominent protopope, was published in febrile times for the Russian Orthodox Church. Within only a few years, the great Raskol (schism) occurred, triggered by the official church’s re-alignment of practices with their Greek roots, a schism which saw the emergence of the Old Believers movement. The fact that this book, which contains a synthesis emerging out of the encounter between Orthodoxy and Latin (Jesuit) education in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, appeared just as this restoration of practices rooted in the Greek tradition was gaining speed might explain why so few copies remain. Ours is one of only six recorded copies worldwide.

Read more...

Yesterday evening, Cambridge Ukrainian Studies hosted a showing of the film ‘Mr Jones’. Directed by award-winner Agnieszka Holland, the film tells the story of Gareth Jones, the journalist who reported on the Holodomor, the appalling famine which killed millions in Ukraine. A pop-up exhibition of books from the UL and MMLL libraries was provided after the film, and the exhibits and captions are shown below. Each title is linked to the item’s iDiscover record. Please click on each image to enlarge it.

“Tell them we are starving” : the 1933 diaries of Gareth Jones

(Kingston, Ontario, Kashtan Press, 2015)

This publication provides facsimile reproductions of three of Jones’ handwritten diaries, covering the period of his Ukrainian trip from 5 March to 24 March 1933. Each diary is provided in facsimile and then followed by a transcription of its contents. The section shown is from the entry for Friday 11 March.

All people say same: khleba netu [there is no bread], vse pukhlye [everyone is swollen]. One woman said “We are looking forward to death”.

Facts about Ukraine

(London : Ukrainian Bureau, 1933)

A staggering lack of belief in the famine and its scale left Jones pitted against the most powerful news agencies and politicians, and caused a shocking lack of awareness in the West of the tragedy. This pamphlet, for example, which was published in 1933 by a pro-Ukrainian group in London, bears no mention of the famine.

Gareth Jones Memorial Fund : list of subscriptions

(UK : [publisher not identified], 1935)

It would take decades for Jones’ reporting to be given the recognition it deserved, but his violent and untimely death in 1935 was greatly mourned. A memorial fund was set up to commemorate him, and this list of subscriptions dates from 2 October 1935. The total amount committed was £1,764.18s.6d. – nearly £120,000 in today’s money. The fund is in use to this day, as the Gareth Jones Memorial Travelling Scholarship, for graduates of the University of Wales.

The 1933 diaries of Gareth Richard Vaughn Jones [exhibition leaflet]

(Cambridge, 2009)

In 2009, the first ever exhibition of Jones’ diaries was held in Trinity College, whose alumnus Jones had been. Cambridge Ukrainian Studies was a co-sponsor of the exhibition, which was reported widely in the media for its success in attracting significant attention to Gareth Jones’ work and courage. The diaries are held with Jones’ other papers in the National Library of Wales.

Naibil’shyi zlochyn Kremlia [The Kremlin’s greatest crime] by M. Verbyts’kyi

(London : DOBRUS, 1952)

Published by the UK section of the Democratic Organization of Ukrainians Formerly Persecuted by the Soviet Regime, this harrowing book includes the personal narratives of survivors (“live witnesses of the famine”) by then based in Britain.

This book featured in a blog post 6 years ago, where the the term ‘Holodomor’ was explained. “[It] became a standard term to describe the Ukraine famine only many years after this book was published. The term used in the book is the standard holod (hunger, famine). The mor added to its end to create the current term is a root relating to death; mor itself means plague/epidemic, but the verb moryty means to kill or to exterminate.”

V dev’iatim kruzi— [In the ninth circle] by Oleksa Voropai

(London : Vyd SUM-u, 1953)

Another example of personal narratives of the Holodomor, this book, as the one above and several others in this list, comes from library of Peter Yakimiuk, a late British Ukrainian whose book collection was donated to the University Library.

Zhovtyi kniaz’ (The yellow prince) by Vasyl’ Barka

(Kyiv : Naukova dumka. 2001)

Mariia: khronika odnoho zhyttia [Maria: the chronicle of one life] by Ulas Samchuk

(Buenos-Aires : Vyd-vo Mykoly Denysiuka, 1952)

(Kyiv : Smoloskyp, 2009)

|

|

|

Barka and Samchuk’s novels are among the most famous Ukrainian literary works about the Holodomor. The 2001 edition of The yellow prince shown was published in the Schoolchild’s Library series, a sign of how the book had become core reading.

The Holodomor reader compiled and edited by Bohdan Klid and Alexander J. Motyl (Edmonton : Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 2012) The University Library and Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics Faculty Library continue to collect material about the Holodomor widely in Ukrainian, Russian, English, and more. A copy of this example is held in both libraries.

——————————————————————————-

Much more material about the Holodomor can be found by using the Library of Congress subject heading Ukraine — History — Famine, 1932-1933 in the catalogue (click here to see the results of a subject browse search, for example).

In Collections and Academic Liaison, we work with many donations of books which add significantly to the University Library’s collections. While they chiefly inspire research amongst readers, they sometimes also inspire holidays amongst librarians. Thanks to Professor Nigel Morgan’s collection of books about North Macedonian churches, I spent an extraordinary week in Ohrid this autumn.

Sveti Jovan Kaneo, overlooking Lake Ohrid.

Professor Morgan’s interest in church architecture and decoration and his generous donations to the UL have featured in an earlier blog post, and that post makes reference to the books he has given us which relate to the Balkans. Ohrid, a major centre of Christian learning and culture from the 9th century and later, under Ottoman rule, becoming a significant city for trade, provides particularly rich church heritage. The church of Sveti Sofia (St Sophia), for example, was transformed into a mosque under the Ottomans and its frescoes covered with plaster. Centuries later, the frescoes – dating as far back as the 11th century – were uncovered. The images below show Sveta Sofia, from the front and also the exonarthex (or outer vestibule) at its rear. Note that the brickwork above the upper gallery in the latter photo has writing incorporated into it.

Before the trip, a week in Ohrid seemed possibly too long, but in practice it barely felt like enough. Having started with a trip across Lake Ohrid to the Sveti Naum monastery, at the sight of whose frescoes the friend I travelled with said, “If we see nothing else in the whole week, this is worth the entire visit,” we found that each church brought yet more jaw-dropping beauty. Below are photos of just some of them: the Sveti Naum monastery main church, two small Ohrid churches across the street from one another (only one of which is ever open at a time; Professor Morgan had tipped me off that the warden of the open one could be asked to lock that and unlock the other), the Sveta Bogorodica Perivlepta church where the fresco sequences are amazingly full and beautiful, and a collection of tickets issued for each visit. One tiny church whose key-holder we managed to track down thanks to instructions (also shown below) on the door to the churchyard was too small to have a ticket… Also included below is one of the mosques in Ohrid; this is the beautiful 18th-century Emin Mahmud mosque.

Taking photos inside the churches was not permitted, so sample images of these need to come from Professor Morgan’s books. These come, with apologies for poor reproductions on my part, from Painting and architecture in Medieval Macedonia : artists and works of art / Sašo Korunovski, Elizabeta Dimitrova (S950.d.201.118) and The Monastery of Saint Naum of Ohrid / Stojan Saveski (S950.e.201.9), and Živopisot na Ohridskata arhiepiskopija : studii / Cvetan Grozdanov (Paintings of the Ohrid archbishopric; S950.b.200.4880). Note that one of the frescoes below (in, of course, an Orthodox church (Sveti Sofia)) shows Roman popes.

The dozens of books about North Macedonian churches donated by Professor Morgan can be found by executing this search in iDiscover.

Istoriia Sankt-Peterburga-Petrograda, 1703-1917 : putevoditelʹ po istochnikam (The history of St Petersburg/Petrograd, 1703-1917 : a guide to sources) is a remarkable piece of work, and our set has just been expanded with four new volumes. The level of detail displayed by the compilers is quite staggering, reflected in the detail of the volume enumeration: our new arrivals are volume 3, issues 5 and 6, each printed in two parts, i.e. 3/5/1, 3/5/2, 3/6/1, 3/6/2. They join 1/1, 1/2, 3/1, 3/2, 3/3, and 3/4. The mysterious volume 2 has yet to be published.

Volume 3, issue 6 (1856-1872), part 2 (1869-1872).

St Petersburg was the capital of Russia for most of its pre-Soviet history, from its foundation in 1703 by Peter the Great, through its renaming to the less German Petrograd following the start of World War 1, to the move of the capital in 1918 to Moscow. For researchers of the city and its history, this still-growing guide to relevant sources is an important holding. Volume 1, issue 1 covers historical sources, general works, reference and bibliographical materials. Volume 1, issue 2 covers published archive material and reference literature about archives. Volume 3, in its now 8 physical parts, covers published legislation. Its first issue started technically early, from 1702 while the overall set is from the city’s birth in 1703. The latest part to come (volume 3, issue 6, part 2) still only takes us up to 1872, leaving one can only wonder how many more parts to come to get us to the 1917 finishing line.

Volume 3, issue 6, part 1 contains 2940 entries (the last is on the rules passed by the Minister of Internal Affairs to the governor of the St Petersburg prison newly opened in 1868), while volume 3, issue 6, part 2 contains a relatively modest 889 entries but is otherwise – and largely – given over to indexes. For these two physical volumes alone, the indexes run to over 400 pages. First we are given a personal name index. As the sample page shown here demonstrates to those with a reading knowledge of Cyrillic shows, the names reflect the diversity of the city. Amongst more standard Russian names (Mel’nikov, Mironov, etc) are many with more Western roots – Meĭsner (Meissner), Miller, Morgan. Some of the individuals with Western surnames are described as citizens of other countries, but many are not and are likely instead to be the children or grandchildren of earlier arrivals to Russia.

The name index is followed by an amazingly detailed and quite diverting subject index, as suggested by the example used in this post’s title. Other examples which caught my eye included: Vice-presidents of the Medico-Surgical Academy–Pensions; Vodka, French; ‘Journey from S.-Peterburg to Moscow’ by Radishchev, A.N.–Ban; Crimean salt–Import by sea; Flautists of the Mikhailovskoe Artillery Academy–Ration allowance. Next comes a “category-hierarchy index”, which presents subject index entries in, as it says, a more hierarchical fashion (the French vodka and Crimean salt, for example, feature here within a wider Trade section).

I should of course also mention here the main entries themselves. Here are some from volume 3, issue 5, part 1, which cover May 1829 and include subjects as diverse as Old Believers, the export of “bread wine” (vodka), the introduction of foreign language teaching in a Kronshtadt school, and provision for the widows and children of deceased members of the Academy of Sciences. Each entry gives full details of the relevant source, often using abbreviations listed at the beginning of the physical volume.

|

|

The set stands at 588:35.b.200.1-2,7-12a, although the four new additions will make their way there only over the next week, via our labellers.

Each August for the last couple of years, we’ve drawn attention to recently received Ukrainian books. Amongst this year’s titles is a wonderfully and mind-bogglingly detailed list of biographical details gleaned, chiefly from obituaries, from a newspaper printed in the city of Lemberg/Lwów/Lʹviv from 1880 to 1939. Four sizeable volumes in, we have only reached 1904.

First, however, here are six new titles which span tragedy and light-heartedness, academic and light reading.

- Bilym po bilomu : z︠h︡inky u hromadsʹkomu z︠h︡ytti Ukraïny, 1884-1939

- an expanded Ukrainian edition of Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak’s work on women in Ukraine first published in English

- Slidy na dorozi / Valeriĭ Ananʹi︠e︡v

- one of two works of fiction here based on the authors’ experiences fighting in East Ukraine

- Karateli / Vlad I︠A︡kushev

- the second book here about the war in Ukraine

- Inshomovna istorii︠a︡ ukraïnt︠s︡iv : 2300 zapozychenykh realiĭ antychnosti ĭ serednʹovichchi︠a︡ u movi, toponimakh i prizvyshchakh

- a dictionary of foreign words in the Ukrainian language and their connection to Ukrainian history, by Kosti︠a︡tyn Tyshchenko

- Unikalʹnyĭ kvytok do Lʹvova : virshi ironichni, satyrychni, komichni, lirychni, a takozh prydybashky, bali︢a︡ndrasy, slovokrutky, prysikanky ta chysta pravda

- a collection of comic verse by Babai (pen name of Bohdan Nyz︠h︡ankivsʹkyĭ (1909-1986))

- #NASHI na karti svitu : istoriï pro li︠u︡deĭ, i︠a︡kymy zakhopli︠u︡i︠e︡tʹsi︠a︡ svit

- an easy-read exploration by Ulʹi︠a︡na Skyt︠s︡ʹka of Ukrainians and those with Ukrainian roots who have had a global impact (a rather good book for those learning Ukrainian!)

Among the group of recent arrivals I pulled out for this post was also some church-related material:

- D-r Kazymyr hraf Sheptyt︠s︡ʹkyĭ–otet︠s︡ʹ Klymentiĭ : polʹsʹkyĭ arystokrat, ukraïnsʹkyĭ ii︠e︡romonakh, ekzarkh Rosiï ta Sybiru, arkhymandryt Studytiv, pravednyk narodiv svitu, blaz︠h︡ennyĭ Katolyt︠s︡ʹkoï T︠S︡erkvy : 1869-1951, biohrafii︠a︡

- a biography of Klymentiĭ Sheptyt︠s︡ʹkyĭ, a Ukrainian Catholic saint who was a Righteous Gentile in World War 2, by Ivan Matkovsʹkyĭ

- Vasylii︠a︡nsʹka Svi︠a︡to-Onufriïvsʹka obytelʹ u Lʹvovi : 500 rokiv istoriï

- a history of the Basilian St. Onuphrius church in L’viv

- Zalyshyvsi︠a︡ tym, kym buv : Kyr Iosyf Slipyĭ : zbirnyk dokumentiv

- a book about and containing works by the Ukrainian Catholic bishop Ĭosyf Slipyĭ

And finally, the set mentioned at the beginning. The newspaper Діло (Dilo) was first produced in 1880. Published initially less frequently, it soon became a daily newspaper, and was the first and most important Ukrainian-language paper in Galicia. During its publication, from 1880 to 1939, the newspaper’s home changed hands and names. Initially, it was Lemberg, the capital of Austro-Hungarian Galicia. Following the First World War, it became part of Poland and was called Lwów. The final issue of the newspaper came out on the 15th of September 1939, in the middle of the Battle of Lwów; shortly after the city would formally take the Ukrainian name of L’viv. The city and region had had a significant Ukrainian population throughout Dilo‘s existence and, as the English summary from volume 2 (see illustration) explains, the newspaper provides a remarkable insight into the lives and make-up of this population.

Each volume provides information for a certain span of years and is divided into two main parts – death notices and bio-bibliographical publications. The latter part captures data about an individual as mentioned in the newspaper, providing quotations/summaries and the section of the paper the mention came in (chiefly Novynky (News)). For a major figure such as the writer Ivan Franko, the list in each volume is long and provides biographical news as well as a list of his written contributions to Dilo. It is, however, the capturing of death and bio-bibliographical information for all individuals whose names appeared in the paper that makes the set such an interesting and important source. Each volume ends with an index for personal names and also one for geographical names.

The first four volumes, of which the latest is the recent arrival, will stand at C215.c.6364-6367. Seven more spaces have been saved for the remainder of the set, assuming a pattern of one volume for each 5 years up until 1939, and we shall have to see whether those spaces are sufficient in the end.

The set so far

Recommendations for new Ukrainian titles are always welcome – please do send them in to slavonic@lib.cam.ac.uk

Last week, I decided to tackle a set about major exhibitions and exhibition spaces in Moscow which had been in the Slavonic cataloguing backlog for some time. How hard a cataloguing challenge could it be? 4 volumes, 6 accompanying discs, 3 accompanying sheets, and 1 accompanying commemorative coin later, I can confirm that the answer was – very.

The coin, front and back.

Cambridge’s copy of VSKhV–VDNKh–VVT︠S︡ is, according to Library Hub (the very new replacement for COPAC), the only one held in the country, which is unsurprising given that it was published in a small run not for general sale. The set was produced to celebrate the 70th anniversary of Moscow’s extraordinary exhibition complex, 2009, although the UL was only able to obtain a copy years later.

After several delays in the 1930s, the enormous VSKhV (Vsesoi︠u︡znai︠a︡ selʹskokhozi︠a︡ĭstvennai︠a︡ vystavka = The All-Union Agricultural Exhibition) was opened in 1939. The vast complex provided visitors with a mixture of permanent exhibition pavilions devoted to the promotion of Soviet production with a pleasure park. The complex was significantly expanded, with dozens more pavilions added, after the Second World War, and in 1959 it was renamed VDNKh (Vystavka dostizheniĭ narodnogo khozi︠a︡ĭstva SSSR = The Exhibition of Achievements of the Soviet National Economy).

The next name change came in 1992, when VDNKh (pronounced “Veh-Deh-En-Kha”) was re-styled VVT︠S︡ (Vserossiĭskiĭ vystavochnyĭ t︠s︡entr = The All-Russian Exhibition Centre). This was its name in 2009, when the set newly added to the catalogue was produced, but 2014 saw the name change once more and the complex was once again officially called VDNKh (unofficially, this had remained its popular name). Post-Soviet changes included the restoration of the famous Rabochii i kolkhoznitsa (Worker and kolkhoz woman) statue designed by Vera Mukhina. The enormous status, with the two figures holding their hammer and sickle together, was first displayed in Paris at the 1937 World Fair, where it stood on top of the Soviet pavilion, opposite the pavilion of Nazi Germany, with the Eiffel Tower as backdrop (image here). It then moved to Moscow, to the exhibition complex, but gradually fell into a state of disrepair. It now stands on a new structure which copies the World Fair pavilion.

The complex is a remarkable place and one which every Moscow tourist should aim to visit (to my shame, I have inexplicably failed to visit it so far myself). To give some idea of what it has to offer, here is a link to a map on its English-language site.

While the efforts to build the complex were clearly gargantuan, the efforts to catalogue the 2009 commemorative set have also felt exhausting. We often deal with “accompanying material”; many books come with loose inserted maps, for example, which go to the Maps Department, and some come with accompanying discs, which go to the general microform collection or to the Music Department (the latter if they are purely audio discs). This set, however, really outdid itself. Each volume had a disc embedded in its front cover, of which 3 were CD-ROMs and 1 a CD. Volumes 1-3 also each came with an accompanying loose sheet of paper (all facsimiles of major documents). Volume 4, called Media, came with 2 further discs (1 DVD and 1 CD) – and a commemorative coin. The Maps Department have kindly agreed to house the coin.

As the set’s record on iDiscover probably shows quite adequately, the wide array of contents presented the cataloguer with a wide array of various titles. Each volume had a title. Each of the 6 discs had a title and a variant title. The coin had a title, of sorts. Add to this the fact that we standardly add Cyrillic variants for the main fields (and I have been very selective here), and the final result is a very, very long record.

|

|

|

|

The set is, of course, still a fine addition to our collections. While it is not an academic publication (and I should really add further subject headings to reflect its heavily pictorial content; there is still some final polishing of the record to do), it provides readers with an eye-catching insight, in Russian and English, into the site’s development over time. Its forewords come from Putin, then in his inter-presidential terms prime minister period, and Iurii Luzhkov (then-mayor of Moscow; he was fired by President Medvedev the following year).

The 80th anniversary of the opening of the complex falls tomorrow, 1 August 2019, and we will be looking out for further publications which mark this latest milestone.

In early 2016, a few months after the destruction of much of Palmyra, our former colleague Josh (now at UC Irvine) wrote about Palmyra and Henri Seyrig. A new arrival, unpacked this week and purchased at the request of a researcher in the Archaeology department, is a good reminder of the Polish contribution to Palmyra research.

The requested book, Palmyra by Michał Gawlikowski, was written in 2010. It is only 131 pages long and well illustrated and provides a general introduction (in Polish) to what was then still a well-maintained site of great importance. The book starts with a history of Polish involvement in the site, dating back to 1959 when Kazimierz Michałowski, the founder and head of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, set up an archaeological team there. The Polish team at Palmyra was later led by Gawlikowski, from 1973, and suspended with the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011. Palmyra ends with a bibliography, with many entries for Michałowski and Gawlikowski; some of those by the latter were co-written with Khaled al-Asaad, once chief archaeologist of Palmyra, who would be murdered by ISIS in 2015.

The UL holds many books about Palmyra, including those listed below by Gawlikowski.

Monuments funéraires de Palmyre (1970; 849.c.99.9)

Le temple palmyrénien : étude d’épigraphie et de topographie historique (S524:01.b.1.6)

Les ‘principia’ de Dioclétien: ‘Temple des Enseignes’ / Michał Gawlikowski ; avec une contribution de Maria Krogulska (1984; S524:01.b.1.8)

Palmyre / J. Starcky, M. Gawlikowski (1985; 517:4.c.95.31)

Do note that a general search in iDiscover for ‘Palmyra’ is not a reliable route for finding all relevant material. The Library of Congress subject heading for the site uses the name of Tadmur (Palmyra was the Roman name). A search for ‘Tadmur (Syria)–Antiquities’, for example, comes up with several score results.

The list of Gawlikowski Palmyra titles above shows that many Polish archaeological titles are published in West European languages. Looking more specifically at what we buy in Polish, most frequently the archaeological books we buy in the language are about work in Poland itself (e.g., Ostrów Lednicki about excavations on Lednicki Island in the central west part of Poland; C202.b.3012) or about the history of neighbouring countries (e.g., Forty i posterunki rzymskie w Scytii i Taurydzie w okresie pryncypatu by Radosław Karasiewicz-Szczypiorski on Roman fortification in Crimea; C202.b.1291).

The strength of Polish archaeology further afield, though, means that titles available only in Polish about sites outside Eastern Europe can still be important acquisitions for the Library. Reader recommendations to help us select which titles to buy are always welcome.

For readers of Polish, 50 lat polskich wykopalisk w Egipcie i na Bliskim Wschodzie (50 years of Polish excavations in Egypt and the Near East) (1986, S512.b.98.69) provides an interesting if now rather dated introduction to the contribution of Polish archaeologists to uncovering and interpreting some of the most important sites in the world. Palmyra is the subject of one chapter, written by Michał Gawlikowski and featuring photos of Kazimierz Michałowski’s own work at the site.

Earlier this week, Vera Tsareva-Brauner gave a talk at the University Library about Ivan Bunin and other Russian émigré literary figures, and this blog post looks at a couple of recent arrivals to the UL about the émigré Russian world.

The Russian Revolutions of 1917 and the ensuing Civil War saw the departure from Russia of many hundreds of thousands of people, many significant intellectual figures among them. The Revolution-related exodus is commonly named the First (or White) Wave. The Second Wave followed World War 2 and the Third Wave took place in the later decades of the Soviet period.

In 1995, the Dom russkogo zarubezhʹia imeni Aleksandra Solzhenitsyna (the Alexander Solzhenitsyn House of Russia Abroad) opened in Moscow. One of the House’s activities is the publication of various research titles and source material about the various Soviet emigration waves. An advanced search in iDiscover for the keywords Dom russkogo zarubezhʹia Solzhenitsyna in the publisher field brings up, at the time of writing, 14 results. Among these, the newest arrival is 1917 god v istorii i sudʹbe rossiĭskogo zarubezhʹi︠a︡ (1917 in the history and fate of Russian émigrés; C215.c.2825), a set of papers from a conference held in 2017. The book’s cover, featuring a detail from Konstantin Iuon’s stunning Novaia planeta painting (which also provided the cover image for the Royal Academy’s Revolution exhibition catalogue), is shown here. The conference papers are divided into three sections:

- 1916 and Russian émigrés : politics, ideology, culture : historical significance and everyday practices

- The intellectual contribution of Russian émigrés to cultural progress (“развитие цивилизационного процесса”)

- The genealogy of memory : family histories, museums, archives, cemeteries of Russian émigrés

Many of the First Wave émigrés wrote accounts of their lives in Russia and abroad, and another recent arrival from another publisher is the 2-volume set of memoirs of Emmanuil Bennigsen (C215.c.2826-2827). Bennigsen held various political positions in Imperial Russia and was closely involved in humanitarian efforts to help Russian soldiers and prisoners of war in World War 1. He fought in the White Army during the Civil War and then emigrated to France for some years before finally settling in Brazil. The memoirs are divided into the separate volumes by the fateful year of 1917.

How might one find similar memoirs in the catalogue? Where a significant emphasis is on the émigré aspect of someone’s life, cataloguers would often add a subject heading along the lines of: Russians–Foreign countries–Biography. (This will appear in the Bennigsen record when the overnight update of iDiscover replaces the poor current record with our improved version.) The Foreign countries section can be replaced by a more specific place name (eg France) where appropriate.

Often the emphasis of the autobiography is on the person’s experience of the October Revolution or Civil War, in which case a heading like Soviet Union–History–Revolution, 1917-1921–Personal narratives, Russian would be used. For non-biographical books, the same subject headings should be applied but without the Biography and Personal narratives subdivisions.

Back to top of the page.

A recent Russian arrival to the University Library takes as its subject tourism in the Soviet Union. Skvoz “zheleznyi zanaves” : See USSR! : inostrannye turisty i prizrak potemkinskikh derevenʹ (Through the Iron Curtain : See USSR! : foreign tourists and the spectre of Potemkin villages; C215.c.1563) is by Igor’ Orlov and Aleksei Popov. Visitors to the Soviet Union normally saw the country in carefully choreographed tours arranged by the state agency Intourist. Such control made sure that the tourists saw strictly what they were meant to see, hence the mention in the book’s titles of Potemkin villages – shorthand for ensuring that appearances support the desired narrative (the term comes from Catherine the Great’s favourite, Potemkin, pulling the wool over her eyes by assembling fake village fronts during a tour).

The Orlov/Popov book joins a growing body of recent books about Soviet tourism. The main subject headings for such books are below, linked to results for the terms in iDiscover.

Looking further back in the UL’s holdings and looking more for material from the time rather than about it, we have the archive of Kent trade union official Herbert Clinch’s 1935 trip to the Soviet Union, which was detailed in an earlier blog post. From the following year, and from the Catherine Cooke collection, we have an Intourist brochure for UK tourists (CCC.54.413). The brochure’s front and back covers and its central pages are shown below.

|

|

|

From 1966, we have another Intourist brochure, this time inviting the British to visit the Soviet Union in the year of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution (2015.9.104). A specific package tour for the anniversary year (the second and third images below, following the front cover) would take in the main sights of Moscow and Leningrad. The remaining images show part of the brochure’s section dedicated to the arts, a general costs list (including services for businessmen and the hire of cars with a driver), and a map of the motor routes available by this stage to tourists driving themselves (advice from the car camping tour page (not shown): “NO NIGHT TRAVEL BY ROAD”).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Orlov and Popov’s Soviet tourism book is their second on the subject. Their first, Skvoz “zheleznyĭ zanaves” : Russo turisto : sovetskiĭ vyezdnoĭ turizm, 1955-1991, looks at Soviet tourists travelling abroad, and will shortly be on order.

Back to top of the page.

As I write and you read the 72nd Slavonic item of the month piece, it can seem that some things will never end. This post, however, looks at the satisfying task of bibliographic closure, with several Slavonic book sets recently completed following the receipt of their final volumes.

Letopisʹ zhizni i tvorchestva N.V. Gogoli︠a︡ (Chronicle of the life and work of N.V. Gogol’) came out over the course of 2017-2018 in 7 volumes. Detailed life chronicles of major figures have always been quite major business in East European publishing, and this lengthy record is a good addition to our literary collections. It is also an eye-catching addition, as the photos show; the cover colour of each volume is even reflected internally in the ink.

|

|

Another recently completed set is also the chronicle of a literary figure – this time, the poet Sergei Esenin (756:37.c.200.56-60a). The final volume, v. 5(2), covers the period from 24 December 1925 to mid-1926. Esenin was found dead on 28 December, a victim of suicide (although theories of murder are still debated). The volume tracks public and private reactions to the poet’s death. Appropriately enough for this post, the concluding entry marks the completion of the final volume of the posthumous publication of Esenin’s collected works in June 1926.

A set published from 2013 to 2019 of the works of the late Moscow conceptualist Dmitrii Prigov now stands at 756:38.c.201.1(1-5) although the five books have been catalogued individually (records here). The final volume, Mysli (Thoughts), contains examples of Prigov’s stikhogrammy – versegrams. The main message (Ин вино веритас (In vino veritas)) is gradually interrupted by the question А В ПИВЕ ЧТО? (AND WHAT IS IN BEER?). The stikhogramma is shown below, beside the cover of this final volume.

|

|

To end with a non-literary example, the Novaia rossiiskaia entsiklopediia (New Russian encyclopaedia (a general encyclopaedia, not focused solely on Russia)) recently saw its final volume published, to the slight surprise of librarians. The first volume came out in 2003 and bore the subtitle “in 12 volumes”. As occasionally happens with such publications, the subtitle’s accuracy wore off with time and it was eventually dropped. The final volume (v. 19(2)) completes the eventual 36-volume set. Its expansion was so significant that we ended up having to put it into two different classmark spans.

The final volume is chiefly made up of additions to the preceding volumes. Some of these are unsurprising (flėshmob (flashmob), for example, is a relatively new term) and Donal’d Dzhon Tramp (pictured) is a recent addition to the world stage. Others are rather surprising for not having been included before: Prigov’s close friend and fellow conceptualist Lev Rubinshtein, Oscar-winner Dzheremi Airons (Jeremy Irons), the authors Govard Filips Lavkraft (H.P. Lovecraft) and Stephen King, and, most curiously of all, the avant-garde.

The Slavonic item of the month feature started in April 2013. The first ever piece marked the 200th anniversary of the death of Field Marshal Kutuzov. The Newton catalogue link in it no longer works, so here is the iDiscover link.

Back to top of the page.

The centenary this month of the start of the Soviet-Polish war of 1919-1920 provides good grounds for a post about the University Library’s Polish history holdings.

Recent arrivals

On the Library’s open shelves, Polish history is to be found chiefly in the dedicated 590 class, whose subdivisions are shown in the screenshot below. Many books are also to be found in the relevant subsections of the World War 2 class (e.g., 539:1.x.60 for Polish war-time political history, 539:1.x.745 for conditions of life in Poland during the war, and so on) and others (particularly the 514:64 and 514:72 classes for East European and European Jewish history respectively). New Polish history arrivals nowadays are more often than not sent to the closed but borrowable class of C200.

We buy broadly across periods, but it is the 20th century which is the primary focus of our acquisitions; this focus also reflects the trend of current publishing. A couple of recently received with an older focus are:

– Pod rządami nieobecnego monarchy : Królestwo Polskie 1370-1382 (Reigned over by an absentee monarch : the Kingdom of Poland 1370-1382; C214.c.9370) by Andrzej Marzec (2017)

– Kronika polska (Polish chronicle; S950.b.201.5337), a 2017 facsimile reprint of the 1597 edition of Marcin Bielski’s chronicle of the history of Poland.

The centenary last year of Polish independence, marking the declaration of the Second Polish Republic in November 1918, prompted a slew of books on the republic, its formation, and its early years, including the title below.

– Polska niepodległość 1918 (Polish independence 1918; C214.c.8946) by Marek Rezler (Poznań, 2018). The book includes maps showing the significant shift of Polish territory between 1918 and 1920, shown below.

| November 1918 | 1920 |

|---|---|

|

|

Jewish history is a particularly significant focus of our collecting in Polish. New books join hundreds upon hundreds of titles about Polish Jewish history in the Library, such as the extraordinary and ever-growing set of Warsaw Ghetto sources Archiwum Ringelbluma (539:1.c.745.224-241,243,243a-243i,243k-243p) and the exhibition catalogue of the Museum of the History of the Polish Jews, bought in English for as broad an audience as possible, Polin : 1000 year history of Polish Jews (2015.12.285). Two new arrivals for our collections are:

– Biografie ulic : o żydowskich ulicach Warszawy od narodzin po Zagładę (The biography of streets : the Jewish streets of Warsaw from their origins to the Holocaust; C214.c.9171) by Jacek Leociak (Warsaw, 2017). The book was accompanied by a large fold-out map showing the Warsaw Ghetto; this can be requested in the Map Room.

– Dalej jest noc : losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski (Beyond lies the night : the fate of Jews in certain areas of occupied Poland; C214.c.8947-8948). The 2-volume set explores the attempts of Polish Jews to avoid detection during the war.

A full list of Polish history books ordered in recent months can be seen here: 201902_Polish HM titles to end month As ever, recommendations and queries are always welcome.

Among recent Ukrainian arrivals was a fine three-volume catalogue of bookplates in the V. Stefanyk National Academic Library of L’viv. Over 12,000 ex-libris from the 20th and 21st centuries were presented to the Stefanyk library by the politician and academic Stepan Davymuk in 2014, and it is the Davymuk collection which is listed so carefully in this set. Many book owners and ex-libris designers who feature in the catalogue are Ukrainian, but the collection also goes well beyond the country’s borders.

The third volume contains an appendix of the relatively few bookplates which are the work of unknown artists. Since the main body of the catalogue is led by artists’ names, the set ends with an index of the owners/commissioners of the bookplates, with the entries following the pattern Name of book owner; Name of artist; number (this last relates to the entries under the artist’s name in the catalogue).

An earlier blog post featured a 1967 postcard sent by a Norwegian commissioner of bookplates to a Soviet designer of them. The former, Thor Skullerud, does not feature in the catalogue, but happily the latter, Rudol’f Kopylov, does. 18 of his bookplates are listed and one is reproduced: see the images below. The reproduced ex-libris was created for V. N. Osokin – likely to be the literary and art scholar Vasilii Nikolaevich Osokin (1919-1981). The banner across the top reads “В мире прекрасного” – “In the world of beauty”.

The fine new set, Ukraïnsʹkyĭ knyz︠h︡kovyĭ znak XIX-XX stolitʹ : kataloh kolekt︠s︡iï Stepana Davymuky (874.b.297(1-3)), makes a good addition to the Library’s already substantial holdings of books about ex-libris – as a search for the subject heading Bookplates will show – and can be called up to the West Room.

In the year 2000, the Institute for Bible Translation produced a rather remarkable volume containing the nativity narrative of Luke’s Gospel (2:1-20) translated into 80 languages of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States.

The Stockholm-based Institute was founded, as the back cover tells us, with the primary purpose of “[making] the Holy Bible available to the non-Slavic peoples of the former Soviet Union”. The book in hand refers specifically to the languages of the Commonwealth of Independent States, or CIS, which – in the year 2000 – included 12 of the 15 post-Soviet states. The three not involved in the CIS were the Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

The book commences with the Greek text of the Luke narrative, followed by the Old Church Slavonic translation and the Russian Synodal one. It then launches into translations of the passage into the extraordinary range of languages listed below (reproduced from the book’s table of contents).

- Ibero-Caucasian languages:

- Abaza, Abkhaz, Avar, Adygei, Andi, Bezhta, Georgian, Dargin, Ingush, Kabardian, Kubachi, Lak, Lezgi, Rutul, Tabassaran, Tsakhur, Tsez, Chechen

- Indo-European:

- Armenian, Baluchi, Wakhi, Kurdish (Kurmanji), Moldavian, Ossetic (Digor), Ossetic (Iron), Rushani, Tajik, Tat, Shugni, Yazgulyam

- Turkic:

- Azeri, Altai, Balkar, Bashkir, Gagauz, Dolgan, Kazakh, Karakalpak, Karachay, Kyrgyz, Crimean Tatar, Kumyk, Nogai, Tatar, Tuvin, Turkmen, Uzbek, Uighur, Khakass, Chuvash, Shor, Yakut

- Finno-Ugric:

- Veps, Karelian (Olonets), Karelian (North), Komy-Zyrian, Komi-Permyak, Mansi, Mari-Hill, Mari-Meadow, Mordvin-Moksha, Mordvin-Erzya, Udmurt, Khanty

- Other languages:

- Dungan, Buryat, Kalmyk, Itelmen, Koryak, Chukchi, Ket, Nivkh, Yukagir, Nganasan, Nenets, Selkup, Enets, Nanai, Evenki, Even

|

|

|

After each translation, brief information about the language and its speakers is given, including bibliographical references about existing Bible translations where these predated the book in hand. There are such references in the majority of cases, thanks chiefly to the Institute’s own efforts, but only a modest majority – 48. The book closes with the English translation from the New King James Version (text here).

The University Library recently received several dozen books from the library of the late Russian drama critic and Cambridge graduate Edward (Ted) Braun. Professor Braun studied in particular the work of Vsevolod Meierkhol’d, commonly anglicised as Meyerhold. Meierkhol’d published an influential journal of literary and critical texts called Liubov’ k trem apel’sinam (Love for three oranges) over the course of 1914 to 1916. The UL had only one volume, so we were delighted to be offered all those collected by Professor Braun. We now hold all but the first issue.

The covers of each of our issues, interspersed with shots of various inserts, are shown below. As a quick glance shows, two chief patterns were used – the abstract motif of earlier issues and the theatrical scene (complete with three oranges) of later issues. Publication appears to have been a little chaotic. Detective work suggests that covers produced for 3, 1915 (never in fact printed; 1-3 were printed jointly that year) were used for later issues. Our copy of 1, 1916, has the “3” on the cover replaced in pencil with a “1” and “1915” inked over to make “1916”. We now hold two copies of the jointly published v. 2-3 of 1916 (Braun’s and our original copy), with both reusing 3, 1915’s cover but each updated differently. The original UL copy has the “No.” replaced with “2” (stuck on) but “1915” still showing. Professor Braun’s stick-on “2” seems to have come off (the cover beneath is paler) and reveals “No.” again, but the “1915” has been updated. The inserts in the gallery below have a brief caption apiece.

Readers can order our physical copies in the Rare Books and Early Manuscripts reading room. We now hold, at F191.c.14.14(1-8a), v. 2(1914)-v. 2-3(1916). Full online access to the complete set is available on the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of World Literature site: http://ruslitwwi.ru/source/periodicals/lubov-apelsin/

Three of the Braun copies have the same signature on the cover – teasingly almost legible. Shots of this are below. Should any reader be able to make the signature out, they are warmly invited to e-mail the answer to slavonic@lib.cam.ac.uk

Another post next week will look at some other new arrivals from Professor Braun’s library, discussing the decision to send some of these to the new Library Storage Facility near Ely.

The final items have recently been added to the Revolution : The First Bolshevik Year online exhibition. I am extremely grateful to the students and librarians who provided many of the captions. Amongst the latest additions is a book which contains a written dedication by the White commander Petr Vrangel’ (commonly Wrangel) – a fascinating re-discovery.

from ‘Russkie v Gallipoli’

Глубокоуважаемому Николаю Николаевичу Шебеко – повесть о крестном пути тех, кто вынес на чужбину и верно хранит национальное русское знамя. Ген. Врангель

To the esteemed Nikolai Nikolaevich Shebeko – a tale about the via dolorosa of those who brought out to a foreign land and faithfully preserve the national Russian flag. Gen. Wrangel

Shebeko had served as a diplomat under the tsar and fought with the Whites. By the time this book, on the Russians in Gallipoli, had been published in Berlin in 1923, Shebeko had settled in France. Wrangel had led the southern White forces and remained a hugely significant figure in emigration. He eventually moved to Belgium, via Yugoslavia where he founded ROVS, the Russian All-Military Union which served to unite émigré officers and soldiers and which attracted a great deal of Soviet state interest. Soviet involvement was certainly suspected in Wrangel’s death in Belgium in 1928 at the age of 49.

Wrangel’s writing proved quite a challenge to decipher, certainly for me. Sincere thanks go to Richard Davies of the Leeds Russian Archive who provided a transcription with little apparent effort and much-appreciated speed.

A higher-resolution image of the dedication can be found here: https://exhibitions.lib.cam.ac.uk/revolutionthefirstbolshevikyear/artifacts/a-trace-of-wrangel/

Last week, two 19th-century Russian books were brought to me by a Rare Books colleague who had found by chance that they had no record in the online catalogue. An invisible title is a librarian’s (and reader’s) nightmare – without catalogue records, we may as well be without books. Now that these two volumes, lost to readers (except those still dipping into the old physical guard book catalogues) for decades, have been found, I thought it would be appropriate to celebrate them in a blog post.

S756.d.86.1 and S756.d.86.2

Nekrasov poems

This little book of over 70 poems by Nikolai Nekrasov (1821-1878) was published in Leipzig in 1869. While it is not the earliest book by Nekrasov held in Cambridge, it certainly counts among the earliest few, and it is always nice to have books printed in the author’s lifetime. The University Library’s 19th-century Russian holdings chiefly came to us through donations, and this volume was donated by one of the most generous donors – Dame Professor Elizabeth Hill, the University’s first Professor of Slavonic Studies. Hill, in turn, had received the book from the literary translator Sidney Jerrold, as the inscriptions here show. Provenance notes have been added to the holdings record (for painful reasons, these do not currently appear on the catalogue), and entries for Hill and Jerrold provided in the main catalogue record (these do).

Stikhotvoreniia N. Nekrasova (S756.d.86.1)

Pushkin in Southern Russia

This book, published in Moscow in 1862, reached the Library not as a donation but through the Soviet-era book exchange programme. This can be discerned from the UL’s stamp on the title page: below the date line, the letter “E” stands out. (“E” means exchange, “B” means bought, and “D” means donation.) Another library stamp on the page also tells us where our copy came from – the Lenin Library in Moscow, now the Russian State Library. Quite how the exchange system worked is not clear to me, but the Leninka, as it is known, assures me through its online catalogue that it still has several other copies (link to Russian catalogue entry).