A Dream Request for Ṣedaqah ben Maqmalyah: Mosseri VI.5

In May 2013, I spent several days at the Genizah Research Unit in Cambridge to study the Genizah material relevant to my doctoral dissertation, written under the supervision of Professor Gideon Bohak. In particular, I examined about thirty Genizah fragments preserving magical recipes and finished products for “dream requests,” i.e. specific divinatory rituals for gaining information in a dream, attested to in the Jewish world from the tenth century onwards and particularly widespread within the Jewish community of Fusṭāṭ.[1] Thanks to Dr. Ben Outhwaite and the team of the Genizah Unit, I was also able to view a fragment from the Jacques Mosseri Genizah Collection, Mosseri VI.5, which is currently undergoing conservation.

The manuscript is a small booklet composed of three paper leaves sewn together, mostly written in Hebrew.[2] Its conservation is rather challenging, since it preserves evidence of an early bookbinding structure including remnants of original thread. This is a rare and significant feature and the conservation team of Cambridge University Library is committed to preserving it, while making the fragment available for viewing by scholars. Mosseri VI.5 has an interesting paleographical and codicological history, with several distinct handwritings, at least three different texts and two personal names, thus suggesting that these papers circulated among a number of people in medieval Fusṭāṭ and were reused for different purposes.

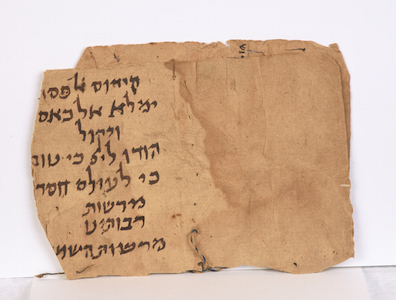

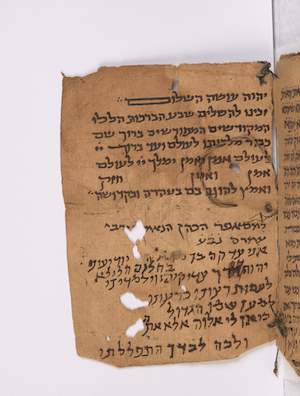

Mosseri VI.5, 1 recto (after rotation)

The first leaf of the booklet, 1 recto (the numeration is mine), exhibits signs of sewing both on its vertical and horizontal axes; on the bottom half of the page presents eight vertical lines of text. The signs of sewing in the middle of the page on its horizontal axis and the longitudinal direction of the text suggest that this leaf belonged to a different handbook – about half the size – before being reused in the present one. The text, probably a benediction, is in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic and reads:

1 קידוס אלפסח

2 ימלא אל כאס

3 ויקול

4 הודו לי׳י כי טוב

5 כי לעולם חסדו

6 מרשות

7 רבותינו

8 מרשות השמים

Textual notes:

Where possible, I have reconstructed the Hebrew letters that were damaged in the original manuscripts. These passages are found between square brackets in the translation.

Line 4: לי׳י stands for the Tetragrammaton.

Translation:

1 Sanctification (qiddush) for Passove[r]

2 Fill the cup

3 and say

4 Give thanks unto the Lord, for he is good

5 because [his] mercy endureth forever (Ps. 118:1/29)

6 under the authority

7 of our masters

8 under the authority of Heav[en] (Birkhat ha-Zimun)

On the verso, the ink either faded or was erased intentionally and unfortunately the text is now illegible. The handwriting, however, seems different from that on the recto and on the other leaves of the manuscript. In contrast with the benediction on the recto, the text on the verso is written on the same axis of the booklet, like the following pages.

Mosseri VI.5, 1 verso

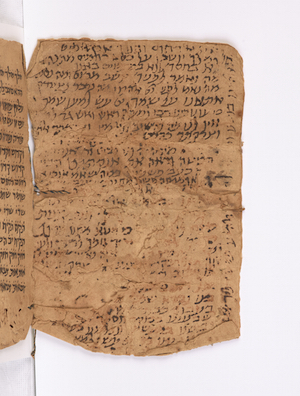

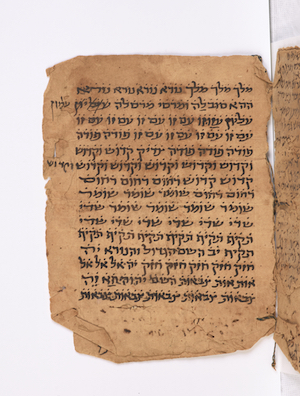

The second leaf presents on both sides (2 verso and recto) fifteen lines written in beautiful handwriting, which differs from those attested on 1. The text, which continues in the third leaf (seven lines in the upper half of 3 recto, blank on the verso), corresponds to the Seven (Adjurations) of Elijah [Sheva de-Eliyyahu, or Sheva Zutarti], a magico-mystical composition in Hebrew and Aramaic, which is related to Hekhalot literature and shares several features with late antique Greek magical texts.[3] The Sheva de-Eliyyahu includes seven adjurations structured around the seven blessings of the Shabbat Amidah prayer, according to the Palestinian rite. The Mosseri fragment preserves only the seventh blessing ברוך אתה יהוה עושה שלום (2 v/15 – 3 r/1), but it is possible that the booklet also originally included the incipit of the prayer. From what remains of it, the version attested in Mosseri VI.5 seems much longer than the text preserved in the other manuscripts known to us. In particular, whoever copied the fragment seems to have personalized the text of the Sheva de-Eliyyahu with additional magical names.[4] It is noteworthy that the Mosseri fragment presents the formula שיעשה שאלתי ובקשתי לי, “that he will fulfill my question and request” (2 v/12), not attested in the other manuscripts and which might indicate a specific interest in divination.[5]

Mosseri VI.5, 2 recto

Mosseri VI.5, 2 verso

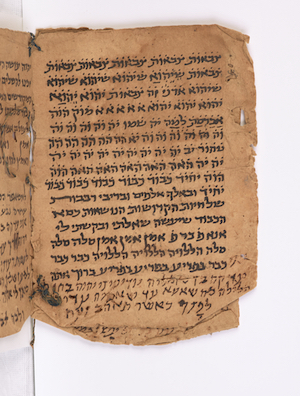

Mosseri VI.5, 3 recto

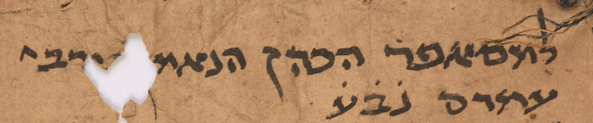

On 3 recto, immediately after the end of Sheva de-Eliyyahu, two lines written by the same hand read: למסאפר הכהן הנאמן בירבי עמרם נ’ב’ע , “to Musāfir the faithful Cohen, the son of ‘Amram, may he rest in heaven”.[6] Musāfir son of ‘Amram, already dead at the time these lines were copied, might have been the person who originally commissioned the booklet with the mystical text or to whom the script was dedicated.

Detail of two lines of text between the end of Sheva de-Eliyyahu and the beginning of the second part of the dream request, bottom half of 3 recto.

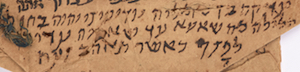

The most interesting section of the manuscript is a dream request written in the right and bottom margins of 2 verso and in the bottom half of 3 recto.[7]

Detail of the dream request written in the right and bottom margins of 2 verso.

Detail of the dream request written in the bottom half of 3 recto.

1 אני

2 צדקה בן מקמליה יודיעיני יהוה בחולם

3 הלילה מה שאצא עד שאהיה צדיק

4 לפָנך כאשר תאהב נצח

5 אני צדקה בן מקמליה יודיעוני בחלום הלילא

6 יהוה ת/דרך צדיקים וילמדיני

7 לעסות רצונו כרצונו

8 ולמען שמו הגדול

9 כי אן לי אלוה אלא אתה

10 ולכה לבדך התפללתי

Textual notes:

Line 1: To render the order of the rows of the dream request, I assign a numeration from 1 to 10, which refers to the lines written in the margins in 2 verso and 3 recto.

Line 2: בחולם is an error for בחלום.

Line 3: The third letter of the third word is very difficult to understand. I transcribe שאצא with the literal meaning of “that I will come out,” but the right reading might also be שאסא or שאעא, an error for שאעשה. Such a writing mistake is not improbable, provided that we read a similar spelling mistake in line 7, i.e. לעסות instead of לעשות. Another possible reading is שאניא, but it does not make sense.

Line 5: The expression בחלום הלילא is added between the seventh and eighth line, under יודיעוני.

Line 6: The copyist writes תרך and then corrects it in דרך.

Line 7: לעסות is an error for לעשות; perhaps רצונו כרצונו is an error for רצונו כרצוני, which is reminiscent of the expression עשה רצונו כרצונך כדי שיעשה רצונך כרצונו in mAvot 2:4.

Line 9: אן is an error for אין; the letter ה in אתה is added above the line: the copyist probably added it afterwards.

Line 10: לכה is scripta plena for לך.

Translation:

1 I

2 Ṣedaqah ben Maqmalyah, inform me YHWH in a dream

3 this night, what I should do so that I may be righteous

4 before you as you eternally like

5 I Ṣedaqah ben Ma[qma]lyah, inform me in a dream this night

6 YHWH the path of the righteous people: and he will teach me

7 to make His will my will

8 and for His great name

9 since I have no God but you

10 and to You only I hereby pray.

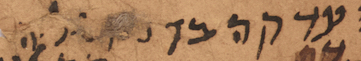

The handwriting characterising the dream request – much rougher than that attested in the section from the Sheva de-Eliyyahu – and the spelling mistakes scattered throughout it suggest that whoever annotated the magical text in the margin was not a trained copyist. The dream request was probably written by the same person that engaged in the oneiric ritual, a certain Ṣedaqah ben Maqmalyah – as it is indicated twice in the text (2 v/15 and 3 r/5) – who might have been the owner of the booklet or the one who assembled it together in the first place. While it is safe to read the first name as Ṣedaqah (צדקה), the matronymic I have reconstructed, ben Maqmalyah (בן מקמליה), is less certain and is not found among the personal names attested in the Genizah magical texts.[8]

Detail of personal name in the bottom margin of 2 verso.

Detail of personal name in the bottom half of 3 recto.

The personal name of the user and the specific object of the inquiry make this dream request particularly interesting and one of the few finished products for this purpose found among the Genizah fragments. While other Jews who engaged in the ritual of dream request in medieval Cairo seemed more concerned with mundane matters, such as finding a hidden treasure, Ṣedaqah performed the oneiric technique for a spiritual-mystical goal, i.e. acquiring knowledge on how to become a righteous person.[9] Despite other dream requests in which several angels and voces magicae are invoked, the finished product in Mosseri VI.5 mentions only the Tetragrammaton and Ṣedaqah declares that he is praying only to the Jewish God. The fact that Ṣedaqah annotated the dream request in the margin of his personal copy of the Sheva de-Eliyyahu suggests that he interpreted this liturgical magical text as a prayer useful for obtaining a response in a dream. The ritual instructions usually found in the Genizah recipes for dream requests are clearly not reported in this finished product. However, we can imagine that Ṣedaqah, after purifying himself and his sleeping place, read the Sheva de-Eliyyahu a couple of times while lying in bed, wrote in the margin his personal recipe and placed the booklet under his head before falling asleep. Whether or not he was shown in a dream the path of the righteous and was guided by an angel to do God’s will, we will never know.

Footnotes

[1] For a survey of the dream requests from the Cairo Genizah, see Alessia Bellusci, Dream Requests from the Cairo Genizah, unpubl. MA Thesis, Tel Aviv University, 2011. On the distinction between “recipes” and “finished products,” see Gideon Bohak, “Reconstructing Jewish Magical Recipe Books from the Cairo Genizah,” Ginzei Qedem 1 (2005), 9-29, especially pp. 12-13, and Id., Ancient Jewish Magic (Cambridge, 2008), pp. 144-148.

[2] On the microfilm, a poor image taken in the 1970s, the signs of sewing are not visible and the manuscript Mosseri VI.5 appears like a bifolium.

[3] Beside the present fragment, Sheva de-Eliyyahu is preserved in five other Genizah fragments, i.e. T-S K21.95P, T-S K21.95T, T-S K1.144, T-S NS 322.21 (Cambridge University Library), Heb. A3.25a (Oxford, Bodleian Libraries), and in the Ashkenazi manuscript Oxford, Bodl. 1535 (Michael 9), fol. 115r/3 – 116r/27. The text is published in Peter Schäfer and Shaul Shaked, Magische Texte aus der Kairoer Geniza, Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism (Tübingen, 1997), vol. II, pp. 22-24 [MTKG II, 22], and in Rebecca Macy Lesses, Ritual Practices to Gain Power: Angels, Incantations, and Revelation in Early Jewish Mysticism, Harvard Theological Studies 44 (Harrisburg, PA, 1998), pp. 381-385. For the Greek elements found in Sheva de-Eliyyahu, see, Gideon Bohak, “Remains of Greek Words and Magical Formulae in Hekhalot Literature,” Kabbalah 6 (2001), 121–34.

[4] On the production of personalised Hekhalot texts, see, Gideon Bohak, “Observations on the Transmission of Hekhalot Literature in the Cairo Genizah,” in Hekhalot Literature in Context: Between Byzantium and Babylonia, ed. by Ra'anan Boustan, Martha Himmelfarb and Peter Schäfer, Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism, (Tübingen, 2013), pp. 213-229, particularly pp. 222-228.

[5] Compare, for instance, to שיעשה פדות והצלה/ מצרה לעמוס שירפא/ וירדוף כל רוח מגופי וכל/ שיד ממני, as in MTKG, II, 22.

[6] The addition of the patronymic to the personal name of Musāfir seems to represent an exception with respect to the other personalised Hekhalot texts from the Cairo Genizah, where the name of the owner and user of the manuscript is not accompanied by any matronymic or patronymic, see, Bohak, “Observations on the Transmission of Hekhalot Literature in the Cairo Genizah,” cit., p. 223.

[7] The dream request was identified by Gideon Bohak, see, Bohak, “Observations on the Transmission of Hekhalot Literature in the Cairo Genizah,” cit., p. 227, n° 41.

[8] Gideon Bohak and Ortal-Paz Saar, “Genizah Magical Texts Prepared for or Against Named Individuals,” forthcoming in Revue des Études Juives.

[9] Two finished products for dream request aimed at discovering the place of a hidden treasure were published respectively in Gideon Bohak, “Cracking the Code and Finding the Gold: A Dream Request from the Cairo Genizah,” in Edición de Textos Mágicos de la Antigüedad y de la Edad Media, eds., Juan Antonio Álvarez-Pedrosa Núñez and Sofia Torallas Tovar (Madrid, 2010), 9-23, and Yuval Harari, “Metatron and the Treasure of Gold: Notes on a Dream Inquiry Text from the Cairo Genizah” in Continuity and Innovation in the Magical Tradition, eds., Gideon Bohak, Yuval Harari, and Shaul Shaked (Leiden and Boston, 2011), 289-320. I intend to publish a third finished product of this type myself.

Cite this article

(2014). A Dream Request for Ṣedaqah ben Maqmalyah: Mosseri VI.5. [Genizah Research Unit, Fragment of the Month, December 2014]. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.8237

Contact us: genizah@lib.cam.ac.uk

The zoomable images are produced using Cloud Zoom, a jQueryimage zoom plugin:

Cloud Zoom, Copyright (c) 2010, R Cecco, www.professorcloud.com

Licensed under the MIT License