A cautionary tale concerning the shipment of ‘sanitary napkins’ from 11th-century Tunis: T-S K3.36

By Nancy Spies

The thousands of written documents found in the Cairo Genizah have shed unrivalled light on the material culture of tenth–thirteenth century Mediterranean life.

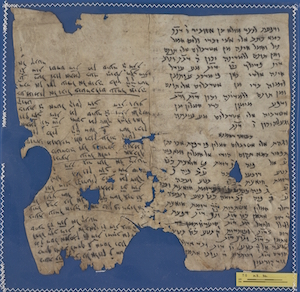

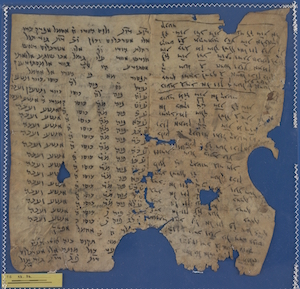

S.D. Goitein’s work on these documents – such as T-S K3.36 which lists items ready for shipping from eleventh-century Tunis, Tunisia – has provided textile historians with extensive information on textiles. Of T-S K3.36, Goitein says that the shipment included “four bales, each of which comprised fifty to fifty-two packages of sanitary napkins …” (Goitein 1967: 334).

As a woman and textile historian, I was immediately suspicious of the idea of shipping sanitary napkins, no matter how fine the fabric. Maimonides, the Torah scholar and physician, stated the following Jewish law in Chapter XIII verse 1 of his 12th-century Book of Women:

‘How much raiment is the husband obligated to provide for his wife? Clothes to the amount of fifty zuz per annum, in the coin current at that time… The new garments should be given to her in the rainy season, so that they would be well worn when she wears them in the dry season; as for worn-out garments, what remains of the original clothes, they are hers to cover herself therewith during her menstrual period’ (Klein 1979: 80).

Oded Zinger, a postdoctoral fellow at Duke University, was able to study T-S K3.36 and has provided valuable insight about what was actually listed there:

Genizah documents often contain passages whose meanings are obscure for us today. The text reads רזמת חיאצת or רזמת חואצת . Rizma/rizmat means ‘bundles’ or ‘bales’. However, since Judeo-Arabic represents both the Arabic ṣād and ḍād with the Hebrew ṣade, the second word can be read either ḥiyāṣa or ḥiyāḍa, from the root ḥ-w-ṣ or ḥ-y-ḍ respectively. Ḥiyāṣa means ‘belt’ or ‘waste girdle’. However, Goitein clearly understood the word as ḥiyāḍa (pl. ḥiyāḍāt), asḥāḍat means to menstruate (ḥāʾiḍa – a menstruating woman, ḥiyāḍ – menses). We get closer to Goitein’s translation when we look at Kazimirski (1860), generally good for middle Arabic terminology, where ḥīḍa is explained as ‘Linge que les femmes emploient par mesure de propreté dans leurs règles’ and finally in Dozy (1881) we find ḥayḍa as ‘chauffoir, linge de propreté pour les femme’ which is exactly what Goitein used in his Studies in Islamic History and Institutions, p. 315. So it is safe to say that Goitein got the meaning from Dozy.

Now, it is up to the scholar to decide whether the meaning here has to do with bundles of belts or sanitary napkins. It seems to me that in the context of robes and hides mentioned elsewhere in the document, belts and waist girdle are more likely than sanitary napkins. Indeed, in another Genizah document (T-S 16.231 verso l.22) we find חיאצה and the editor there translated it as belt (Frenkel 2006: 348, 355). To pursue the matter further, I would look at Lane (1863) that has it (on p. 670a) as a waist belt for wealthy women adorned with jewels and points to Dozy’s Dictionary des Noms des Vetements chez les Arabes, pp. 145–7, which is where I would go next (Oded Zinger, personal communication, 15 May 2014 and 14 Nov 2014).

At this time, Tunisia was a well-known exporter of leather goods, so that adds extra weight to the idea that this shipment was of belts, not sanitary napkins. It could, however, be speculated that these belts were meant as a means to secure sanitary napkins, as women of a certain age now remember from their teenage years. It might also be possible to extend the meaning to include the leather ‘bikini’ bottoms depicted on the woman exercising in mosaic at the Roman villa in Piazza Armerina in Sicily, but that is purely hypothetical on my part. We also know, again from Maimonides, that women wore trousers: ‘… and find her rising from the couch and putting on her trousers…’ (Klein 1979: 15). Women would have been able to wear any sort of arrangement for securing sanitary napkins, made from old clothing, safely.

I would conclude, then, that the shipment from Tunis was a bundle of leather belts and not sanitary napkins. This has proven to be a true cautionary tale in taking translations always at face value.

Cambridge University Library T-S K3.36 recto

Cambridge University Library T-S K3.36 verso

Bibliography

Dozy, R.P.A. (1845) Dictionnaire Détaille des Noms des Vêtements chez les Arabes. Amsterdam: Jean Müller.

Dozy, R.P.A. (1881) Supplement aux Dictionnaires Arabes. Leiden, E.J. Brill.

Frenkel, Miriam (2006) The Compassionate and the Benevolent: The Leading Elite in the Jewish Community of Alexandria in the Middle Ages. Jerusalem.

Goitein, S.D. (1967) A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, vols. 1–6. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kazimirski, A. de Biberstein (1860) Dictionnaire Arabe-Francaise. Paris: Maisonneuve et Cie.

Klein, Isaac (1979) The Code of Maimonides. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lane, Edward William (1863) Arabic-English Lexicon. London: Williams and Norgate.

Cite this article

(2015). A cautionary tale concerning the shipment of ‘sanitary napkins’ from 11th-century Tunis: T-S K3.36. [Genizah Research Unit, Fragment of the Month, April 2015]. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.8236

If you enjoyed this Fragment of the Month, you can find others here.

Contact us: genizah@lib.cam.ac.uk

The zoomable images are produced using Cloud Zoom, a jQueryimage zoom plugin:

Cloud Zoom, Copyright (c) 2010, R Cecco, www.professorcloud.com

Licensed under the MIT License

- See more at: http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/Taylor-Schechter/fotm/april-2015/index.html#sth...